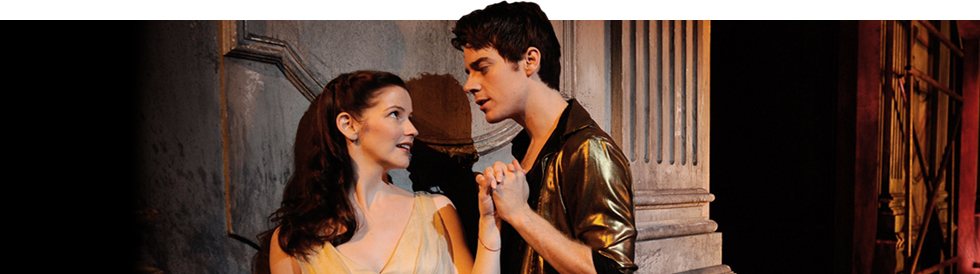

Romeo and Juliet

September 15

November 11, 2010

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Gale Edwards

September 15

November 11, 2010

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Gale Edwards

by Peter Holland

It's fascinating how Shakespeare plays show you how you change as you get older. I can remember when I thought Romeo and Juliet was the great tragedy of adolescent passion. Now, part of my mind wants to say 'Damn kids!' and I can end up, at some productions, feeling sorrier for their parents.

When Shakespeare read Arthur Brooke's long and really rather boring poem The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet (1562) and saw the possibilities of turning it into exhilarating drama, he also found that Brooke thought his young lovers were indeed damned. Brooke blamed them for:

...thralling themselves to unhonest desire, neglecting the authority and advice of parents and friends, conferring their principal counsels with drunken gossips and superstitious friars (the naturally fit instruments of unchastity), attempting all adventures for th'attaining of their wished lust...abusing the honorable name of lawful marriage...finally, by all means of unhonest life, hasting to most unhappy death.

Brooke's poem is perhaps not quite as moralistic as this passage suggests. But at the heart of Shakespeare's play, as throughout his work, is a deep anxiety about making judgments, moral or otherwise. The mad haste which drives the action onwards, barely giving anyone a chance to think or reflect, the impetuosity that prevents the characters from taking Friar Laurence's advice ("Wisely and slow. They stumble that run fast"), also means that it is difficult to blame these "star-crossed" figures for what they are driven to do.

Allocating responsibility matters less than accepting that, as the Prince states so fiercely, "All are punished," suffering through their grief—and that includes the Prince himself, for, while the Prologue told us that this is a tale of "Two households, both alike in dignity," the Prince's own family is the third to be involved: Mercutio and Paris, two of the slaughtered young, are his kinsmen. Over and over again, the characters would like to say, with Romeo, "I thought all for the best." But none of the play's children survive, except perhaps Benvolio, the man whose name means "I wish well" but who vanishes from the play after Romeo kills Tybalt, the point when there seems no longer a possibility of drawing back from the rush to tragedy.

These hectic events of mid-July, which last only from a Sunday to a Thursday—and the play is surprisingly precise about its time of year and days of the week—are increasingly out of control, subject to accident, chance, and that terrifying delay, the single minute that causes the final tragedy—for, if Romeo had only waited another minute before taking the poison, Juliet would have woken up in time. But little in this play is ever 'in time'; this is the great drama about being short of time, out of time, never timely.

Instead, Romeo and Juliet teases us with shapes and repetitions that tantalizingly suggest order. Take the way, for example, that the Prince appears three times, at the beginning, middle and end of the action, each time responding to civil disorder; or the shapely poetic form of the sonnet that is both the structure of the opening Prologue and of the first exchange between Romeo and Juliet, and then is heard in fragments of quatrains and couplets right through to the play's end; or the way the Nurse three times interrupts the lovers' attempts to be together (at the party, in the balcony scene, and in that terrible dawn of parting). Such devices set up resonances and echoes that remind us how the fluidity of the action, its immediacy and disorderly energies, are also part of something that Shakespeare here seems to define as the "stars" that Romeo defies.

Mercutio's death and the Nurse's urging Juliet's marriage to Paris leave the lovers most completely alone, in a space where they make their own choices. The result is that moral judgments prove unexpectedly true: it is over Juliet's feigned death that Friar Laurence pontificates "she's best married that dies married young," never guessing how appallingly it will become the case. Now that our society seems particularly full of people offering to force their own moral views on the rest, Romeo and Juliet can, in its reminding us of the inefficacy of such actions, prove newly timely.

Peter Holland is the McMeel Family Professor in Shakespeare Studies and Chair of the Film, Television and Theatre Department at the University of Notre Dame. His most recent books include English Shakespeares: Shakespeare on the English Stage in the and From Script to Stage in Early Modern England. The following scholar notes were first published in bill for CST's 2003 production of Romeo and Juliet.

Peter Holland is the McMeel Family Professor in Shakespeare Studies and Chair of the Film, Television and Theatre Department at the University of Notre Dame. His most recent books include English Shakespeares: Shakespeare on the English Stage in the and From Script to Stage in Early Modern England. The following scholar notes were first published in bill for CST's 2003 production of Romeo and Juliet.