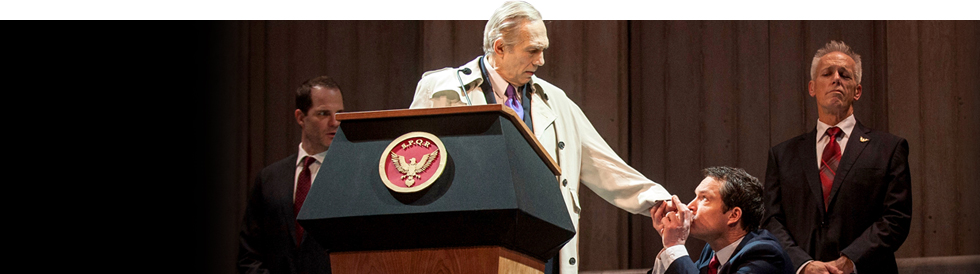

Julius Caesar

February 5

March 24, 2013

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Jonathan Munby

February 5

March 24, 2013

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Jonathan Munby

The Story

All Rome takes to the streets in celebration: the great general Julius Caesar returns triumphant from his victory over Pompey. In a republic where no man may reign, the Senate now moves to place a crown on Caesar’s head. But to those who fear a ruler’s absolute power, the lifeblood of their republic, they say, rests upon the death of this one man. Led by Cassius, the men conspire to assassinate Caesar before he can be proclaimed king. Requiring the support of a high-minded colleague like Brutus to lend respectability to their plot, it is left to Cassius to persuade his friend and ally to their side.

Caesar dismisses the nightmares of his wife and the prophecies of a soothsayer, and ventures out to the Senate. It is the ides of March. Soon the great Caesar, conqueror of a vast empire, will lie silenced in his blood, surrounded by his murderers—the senators of Rome.

Brutus explains the necessity for Caesar's death to a bewildered crowd, calmed until Caesar's ally, Antony, with passionate words transforms them from frightened fragments into a murderous mob. Forced to flee Rome, Brutus and Cassius gather armies. Octavius, Caesar's nephew and heir, alongside Antony takes control of Rome, and together they plan the execution of all who threaten their power. It will be at Philippi that Brutus faces the spirit of Caesar—and Rome, its fate.

In Performance

Although Julius Caesar was not published until 1623 in the First Folio, it is believed to have been written and first performed in 1599. The play was immediately popular, and was often alluded to in other works by Shakespeare’s contemporaries. One of the shorter plays in the canon, it—like all of Shakespeare—is rarely performed in its entirety, Throughout the past four centuries, as audience perceptions of patriotism, monarchism and honor have evolved, so have directors’ cuts and performers' interpretations. The role of Cinna the Poet, for example, first excised in 1719, was not restored in most productions until the twentieth century.

One of the single-most important productions of Shakespeare on the American stage was directed by Orson Welles at New York's Mercury Theatre in 1937. Opening days after the pre-WWII alliance of Italy, Germany and Japan, Welles used the widespread anti-fascist, pro-democracy sentiment that engulfed the country. The best-known film of Julius Caesar is the 1953 version, starring the young Marlon Brando as Mark Antony.

At Chicago Shakespeare Theater, Artistic Director Barbara Gaines staged the company’s first full-length production of the play in 2003, with a cast including Guy Atkins, Kevin Gudahl, Scott Jaeck, Linda Kimbrough and Scott Parkinson. In this past year in the UK, two critically acclaimed productions have emerged, including director Greg Doran’s at the Royal Shakespeare Company, set the tyrannical feud in modern-day West Africa. At London’s Donmar Warehouse, staged by opera director Phyllida Lloyd, the all-female production was set within a prison, where inmates decide to stage a play.

Shakespeare and the Romans

Shakespeare deviated remarkably little from his primary source, Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romanes, translated into English twenty years earlier by Sir Thomas North in 1579. In comparing prominent figures from Greek and Roman history, Plutarch viewed history as a compendium of the deeds of great men, portraying the characters and ambiguities of these individuals.

Tudor England’s understanding of Roman values and philosophy was derived largely from the writings of the great orator Marcus Tullius Cicero--one of very few in the Republican period to achieve consular status despite a humble lineage. His Epistles, providing a detailed, if biased, record of the last decades of the Republic were well known in Latin, and used to teach writing in England’s grammar schools. Cicero actively supported Pompey against Caesar. Later he befriended Brutus and Cassius in their fight against Antony and Octavius. He was a staunch Republican, and defended the events of the Ides of March to the end of his life though he did not participate in the conspiracy to assassinate Caesar, and his views on that subject are sketchy at best. He hated Antony, and his extant speeches provide biting evidence of his antipathy.

The third influential source for Julius Caesar was Appian, born in 95 A.D. Appian worked in the Roman civil service, and later wrote a 24-book version of Roman history. In The Civil Wars, translated into English in 1578, Appian provided Shakespeare with a balanced description of Caesar's behavior after the death of Pompey. His work, unlike Cicero's, makes no judgments about the motives of the conspirators but, like Cicero's, contributes to Shakespeare's Antony, who Appian portrays as bold, subtle and cunning.

Treason in the Court

In 1598 Robert Devereux, the second Earl of Essex, sent a letter to an acquaintance in which he queried, “When the vilest of indignities are done unto me, doth religion enforce me to sue? Or doth God require it? Is it impiety not to do it? What, cannot princes err? Cannot subjects receive wrong? Is an earthly power or authority infinite?”

The target of Essex’s fury was Queen Elizabeth I. The indefinite answer to his speculation, which any citizen of England could have given him at the time, was that his sovereign’s power was irrefutable, having been bestowed by a Divine magnate. Treason was viewed as an act that threatened the very fabric of the established order, human and divine. The 66-year-old monarch was fully capable of reading between the lines of plays presented to her court and her subjects—including one portraying an aging Roman ruler – a pompous tyrant, susceptible to flattery, and unwilling to acknowledge his own failings. Only a year before, her favorite at court, Essex, had written his daring letter--and in another year would lead a group of armed men to the very door of her bedchamber. Like Caesar, she witnessed the unreliable nature of those in whom she placed her confidence and affections. Unlike Caesar, she outlived their conspiracy.