AS YOU READ THE PLAY

8. Character Study

Like Shakespeare’s plays, many of the characters in Bartlett’s play are based on real people. However, unlike studying one of Shakespeare’s characters, we have the benefit of being able to access a huge amount of information very quickly as we begin to understand the foundation upon which Bartlett created his fictional story and characters.

Choose one of the members of the Royal Family to follow throughout the play: Charles, Camilla, William, Catherine (Kate) or Harry. Before you begin studying the play, begin collecting information on your chosen family member, which might include articles (of varying sources—tabloids vs. newspapers), images, videos, and their own websites. As you research, formulate answers to the following questions:

- Age?

- Born and raised where?

- Siblings?

- Royal title?

- Interests and passions? (To what causes does your character devote the most time and efforts?)

- Public perceptions of your family member?

- How grounded in reality—or unmerited—are these public perceptions?

- Based on your research, what are four words that summarize your family member?

Create a small group with your classmates who chose the same family member as you. Compare notes and come to consensus where your findings differ and on your four descriptors. Then, as a group, present your character to the class, speaking in first person as your character.

As you read the play, follow your chosen character closely, and respond to the following questions in writing. Be sure that your answers to these questions are strongly grounded in evidence from the text:

- Significant decisions that your character makes in the play?

- What your character says about him/herself? (Hint: look closely at the soliloquies!)

- What other characters say about your character?

- Based on the fictional reality that Bartlett has created, what are four words that summarize your family member?

Come back together with your small group. Compare what you’ve learned about your character through the lens of the play with your original research. What are the similarities, and where did Bartlett choose to diverge in his storytelling? Compare your descriptors of the actual person versus the character in Bartlett’s play—how closely do the characters that Bartlett imagines resemble the actual members of the Royal Family? Share your findings with the class.

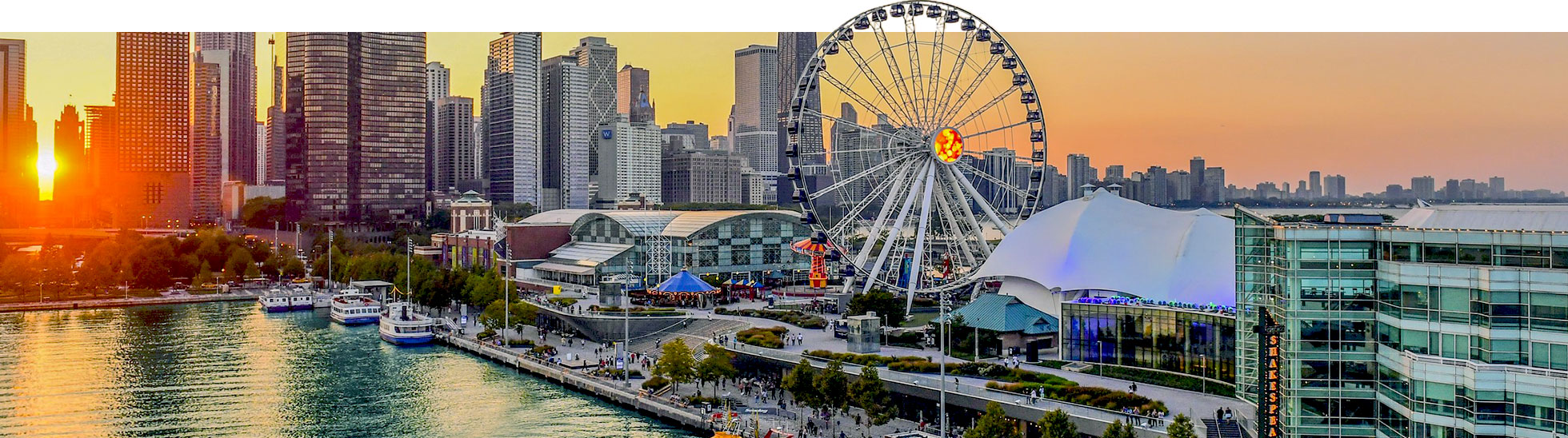

Possible extension: As you watch Chicago Shakespeare’s production, study the actor playing your chosen character. That same day of your performance (while it’s still fresh in your memory), write down your observations of the actor’s interpretation of the character. How does the actor in this production differ from what you researched, and what you imagined as you read the play? What choices did the actor make that enhanced your understanding of the character?

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS R3

9. Echoing Fears

King Charles III begins just after the funeral of Queen Elizabeth II, and all in the Royal Family are grappling with this new reality. Charles asks his family to leave, so that he might have a moment alone before his first meeting as King with the Prime Minister. After his family departs, Charles delivers the first of many soliloquies, and in this one, the audience is privy to some of Charles’ deepest fears. As a class, read through his soliloquy (beginning with, “At last. I needed room for thought to breathe” through “One is protected from the awful shame of failure.”)

- Read-through #1: Read the speech aloud, switching readers each time you come to a punctuation mark. Circle any words or phrases that are confusing to you and discuss what they might mean as a class.

- Read-through #2: Read through the speech again, this time switching readers each time you come to a full stop (a period, question mark, or exclamation point). As you hear the speech a second time, listen for words and phrases that reveal Charles’ emotional state—his hesitations about the duties that await him as King, his longing to become King, and his fear that he might fail once he finally becomes King. Circle these words or phrases.

- Read-through #3: This time, rather than a linear read, the class will speak aloud the words and phrases you circled in read-through #2. Anyone can speak their contribution at any time, and words and phrases can be repeated when multiple students have chosen them. Once all have added a word or phrases to reading, discuss what this exercise reveals about Charles at this very first moment in the play. What might it foreshadow about the events of the play?

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS R4

10. Character Tactics

Characters always speak and act to achieve what they want (just as we do in everyday life). The different strategies they use to get what they want are called “tactics.” In Act 1, scene 3, King Charles and Prime Minister Evans want very different things. With the steps below, explore the various ways in which Charles and Evans try to get what they want.

[To the teacher: divide the first part of Act 1, scene 3—page 16 to 20, stopping at Charles’ line “And so you have, we’ll meet next week”—into smaller chunks, about a page of text each. When you assign excerpts to your student pairs, multiple pairs will be working on each excerpt, which will highlight the concept of multiple interpretations when they perform their scenes for one another.]

- As a class, listen as a couple of volunteers read the full scene aloud. Then, learn and practice the following tactic gestures:

- Hook – Extend the arm and curve the fingers toward your body. Move the hand toward the body.

- Probe – Point the index finger of one hand. Extend the arm forward. Move the finger around and forward as if it is digging into something.

- Deflect - Extend the arm and have the palm facing upwards as if pushing something away.

- Punch – Make a fist and punch the air in front of you.

- Flick – Join your fingertips together and then quickly extend your fingers fully, as though you are flicking water on someone.

- With a partner, decide who will read each character, and read your assigned scene excerpt aloud. Together, decide which tactic best matches what your character wants to achieve in each line. If you feel a character changes tactics within a line, you can choose to make two different gestures. (Remember: there is no one “right” answer here. Ten different groups may choose to interpret these lines ten different ways, since dramatic texts always allow for multiple interpretations.)

- Read the scene excerpt while doing the gestures. Discuss which gestures don’t work as well, and sub in others until you feel like you’ve found the tactic that for you, best connects to each part of the text.

- Back with the full class, watch several scenes and discuss:

- Which gesture/s did each character use most in this scene?

- What might that tell you about the character or situation he/she is in?

- Do the tactics the characters use change throughout the scene? Why is that?

- Do you understand the scene or characters differently as a result of this exploration?

- Were there times when two or more groups chose a different tactic for the same piece of text? What was the effect of each?

Possible extension: Ask the students if they felt there was any tactic they felt was missing. Choose one or two tactics and create a gesture for them. Go back to the scene and add in the additional tactic/ gestures.

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS L3, R6

“To the Honorable Prime Minister”

“Please look at this, it came today.” In Act 2 (page 28), the Prime Minister shares the King’s letter with the Leader of the Opposition, which contains Charles’s determination not to sign the bill passed by Parliament. Very Shakespearean—a letter that we can surmise the contents of, but never see. So, what if you were now King Charles III and writing to your Prime Minister at this moment in the play—in perfect iambic pentameter? What would your letter contain, and how might you express your intentions? Will your letter be brief and to the point, or filled with every argument you can muster? If the former, go ahead and write the entire letter! If the latter, write a section in iambic pentameter and then outline the points you think that Charles would have to make…

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS W4, W9

11. Visualizing Charles' Moral Dilemma

Towards the end of Act 2, Evans revisits Charles to urge him again to sign the bill restricting freedom of the press. Charles still refuses to sign and explains his dilemma in a monologue (beginning with “That’s right, and in good conscience I have thought…” on page 39 of the script.)

While one brave volunteer reads the speech aloud, close your eyes and listen closely to the figurative language Charles uses to explain his position. Each time you hear something in the speech that conjures up a picture in your head, raise your hand. While a new volunteer reads the monologue again, open your eyes and have the text in front of you to mark up. Circle all words and phrases that stand out to you as you listen.

In small groups, agree on a single word, phrase or line that conjures up a vivid image for you, and then bring that line to life through a tableau—a “living sculpture” of bodies. Take turns directing, or “chiseling,” the sculpture. Revise until the sculpture closely represents the figurative language you’ve chosen. Present your final sculpture to the rest of the class. How does your understanding of the monologue change through an examination of these tableaux? What does the language reveal about Charles’ tone in this speech? Is there a pattern or a theme among the lines your group and others chose to represent through tableau?

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS R4, L5

12. Exploring Rhetoric and Poetic Devices

In the beginning of Act 3, Prime Minister Evans and King Charles deliver back-to-back addresses to the public on the stand-off between the Parliament and the Monarchy. Just as Shakespeare’s plays are filled with rhetorical and poetic devices that add emotion, punch, flavor, intensity to his plays and characters, so too has Bartlett chosen to put many of these devices to work for the characters in this play. Throughout both speeches, you’ll find:

- repetition of consonant sounds (alliteration)

- repetition of vowel sounds (assonance)

- lines in which every word has only one syllable (monosyllabic lines)

- two opposing thoughts that are expressed by parallelism of words that are the opposites of each other (antithesis)

In pairs, read ALOUD (it’s imperative or you won’t hear the repetition of sounds!), and mark the text whenever you hear: alliteration, assonance, monosyllabic lines, or antithesis. As a class, listen to one or two readings of each speech, encouraging your classmates to over-emphasize the devices they have identified.

- When the devices were overemphasized, did you hear anything in the speeches that you didn’t hear before?

- How would you describe the tone of each speech?

- Based on these two speeches alone, do you find yourself siding more with the Prime Minister or the King, and why?

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS R4

13. Discovering Embedded Stage Directions

In Act 3 (page 51), Charles is visited in the middle of the night by the Ghost of his first wife, Princess Diana. In response to the Ghost, he says:

CHARLES

The greatest King?

But stop, please wait! I didn’t understand!

Explain!

But no, it drifts away, like mist at dawn.

Oh god, if anyone did see me now

Their brand new king, who, sleepless runs towards

The made up nonsense in his head, but yet…

She is quite beautiful I know the walk.

The Ghost goes.

Just like Shakespeare, Bartlett writes two kinds of stage directions: those like “The Ghost goes” but then others that are “embedded” in the lines of a character’s speech. Charles’s part above is full of such embedded stage directions—both to the Ghost and himself. In groups of three, take on the roles of the Ghost, Charles and a director. As Charles says the lines above, the two characters (with the help, of course, of their director!) must each figure out when to move and how to move. Play with this moment for a while in your group, and then come back together as a class to see a few different interpretations of Bartlett’s multiple stage directions in just these few lines of text.

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS R1, SL4

14. Scene Lab: The Eleventh Hour at Parliament

[To the teacher: This activity, based on an exercise developed by actor Michael Tolaydo, may take two class sessions to complete, but is well worth it! The exercise is a performed group scene. This is not a “staged” performance, so there should be no heavy focus on acting skills; rather, this should be approached as a learning experience involving exploration of plot, character, language, play structure, and play style. The script should be photocopied and typed in a large font [at least 13 point], with no text notes or glossary, and enough copies for every student in the classroom. In selecting readers for the speaking roles, it is important to remember that the play is not being “cast,” but rather that the students are actively exploring the text. The process of getting the scene off the page and on its feet enables students to come to an understanding of the scene on their own, without the use of notes or explanatory materials. A familiarity with the scene and the language is developed, beginning a process of literary analysis of the text and establishing a relationship with the play and its characters.]

Sometimes, the most action-packed and exciting scenes in a play are difficult to read on the page because there is not yet a picture to accompany the words—and though good proficient readers can create those pictures in their minds as they read, some may struggle with this kind of rich visualization. This is where a “scene lab” comes in very handy, especially when a scene involves many characters and a lot of physical action, such as Act 3, scene 6, or “the eleventh hour at Parliament.”

- Step One: Assign students to read the scene through for the first time. (Choose a student to read the stage directions as well.) While the scene is being read, the rest of the class listens rather than reads along, so no open books. If you come across unfamiliar words or phrases, don’t worry about the correct pronunciation. Say them the way you think they would sound. (Later, you can take a class vote on the pronunciation of any words that cannot be located in the dictionary.)

- Step Two: Follow the first reading with a second one, with new readers for each part—not to give a “better” reading of the scene but to provide an opportunity for others to expand their familiarity with the text, and possibly gain new information or clearer understanding of a particular passage. After this second reading, engage in a question-and-answer session. Answers to the questions asked should come only from the scene being read, and not rely on any further knowledge of the play outside the scene at hand. Some examples of the questions to be discussed: Who are these guys? Where are they? Why are they there? What are they doing? What are their relationships to each other? What words don’t we understand? What else is confusing in this scene? If there is disagreement, take a class vote. Majority rules! Remember, there is no one right answer, but a myriad of possibilities—as long as the conclusions are supported by the text. After this, you may choose to read the scene a few more times, with new sets of readers, followed by more questions.

- Step Three: The “fast read-through” is next. Stand in a circle; each student reads a line up to a punctuation mark and then the next student picks up. The point of this is to get as smooth and as quick of a read as possible, so that the thoughts flow, even though they are being read by more than one person—much like the passing of a baton in a relay race.

- Step Four: Before we put the scene “on its feet,” search the text for signals that help you know how to move and speak to create a coherent story. There are the actual stage direction provided by the playwright, but other stage direction can be found in the character’s own lines or may be spoken by another character. (e.g. when the Speaker of the House says, “Please will someone, before we vote, go see / What causes this infernal knocking there!,” it’s a good indication that someone might begin to move towards the door.) In addition to looking for these signals in the script, ask yourself these questions:

- Where do you imagine the audience to be sitting?

- How many characters are on stage at the start of the scene?

- Where and how will you position each character and the members of Parliament? (You may want to reference a diagram of the House of Parliament as you’re making your staging decisions.)

- Which characters make entrances and/or exits in the scene? From where do they enter and where will they exit?

- How does each character walk?

- How does each character talk?

- What furniture or properties (props) might be needed for the scene?

- Step Five: The final step is to put the scene “on its feet,” using the signals and choices you’ve discussed as a class. Select a cast to read the scene, while the rest of the class becomes members of the House (and helps to direct the scene.) No one is uninvolved. There are many ways to explore and stage this scene—there is no one “right” way, and everyone’s input is important. After the advice from the “directors” has been completed, the cast acts out the scene. After this first “run-through,” make any changes necessary, then perform the scene again using the same cast or a completely new one.

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS R7, SL1, SL2

15. Embodying Figuative Language

CHARLES

Unlike you all, I’m born and raised to rule.

I do not choose, but like an Albion oak

I’m sown in British soil, and grown not for

Myself, but reared with single purpose meant.

While you have small constituency support.

Which gusts and falls, as does the wind

My cells and organs constitute this land

Devoted to entire populace

Of now, of then, of all those still to come.

Charles, like a true Shakespearean character, speaks at moments like these in this play in heightened language, full of imagery, simile and metaphor. Here, as he contrasts himself to the members of Parliament, Charles creates a picture—which we can bring to life. Dividing these nine lines into three different chunks (Lines 1-4; 5-6; 7-9), in groups of four to five, work on your lines and create a tableau—a wordless, motionless picture composed with your bodies. Come back to the larger group and look at one another’s tableaux. Now, as a class, create a complete “triptych” out of the three chunks, which represents the entire arc of Charles’s lines.

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS L5, SL1

16. Inside Kate's Psyche

At the top of Act 4, scene 3, Kate delivers her first and only soliloquy in the play, revealing the working-class and feminist underpinnings that appear to motivate much of her action in the play. As a class, read the speech, switching readers at each punctuation mark. Then, read through the speech again, switching readers at every period. Kate covers a lot of ground in this short speech. As a class, decide where the “beats,” or gear changes, occur in this speech, and mark the changes with a slash in your script.

Divide into as many groups as beats you’ve identified in the speech. Each group taking one beat, create a “tableau”—a visual picture using your bodies, like a frozen snapshot—that represents your beat. You can choose for your tableau positions to be as literal or as figurative as you wish. Here are a few other hints to keep in mind:

- Create different levels with your body positions—low, medium, high

- Find depth in the tableau. (Avoid the straight line…)

- Use proximity and distance as tools to convey meaning

Take turns sharing your tableaux with your classmates, discussing:

- What do you notice in each tableau?

- How did incorporating levels, depth, and distance help to shape the tableau?

- To the tableau-makers: What did the group intend to communicate?

- To the audience: Observing their picture and hearing their intentions, what aspect/s could be made clearer? How would you suggest that they continue to sculpt their tableau?

- To the entire class: What does this exercise reveal about the character of Kate? What do we learn about her motivations in this speech—and through this exercise?

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS R3

17. The Play's Final Moments

As the Archbishop prepares to place the crown on William’s head in the final moments of the play, Bartlett has included a flurry of brief stage directions, indicating the basic movements of the Archbishop, Charles and William. It is an actor’s job—and a good reader’s job—to imagine the emotional rollercoaster that each character is experiencing. Assign one of these three characters to each third of the class. For each of the following stage directions included in the play, write a sentence or two (in the first person) about what your character is thinking and/or feeling as each action occurs:

A choir sings.

The Archbishop goes and gets the crown.

He brings it forward to William.

Charles suddenly stands—a consternation. This isn’t supposed to happen.

He goes and looks at the crown.

The choir stops singing.

Charles reaches for the crown. The Archbishop is unsure.

Glances at William. Then gives the crown to Charles.

A moment.

With three student volunteers, one for each character, read the stage directions aloud, followed by the internal thoughts of each character. Listen to at least three interpretations of each character’s inner thoughts and discuss what you discovered about the characters and this moment in the play.

CONSIDER COMMON CORE ANCHOR STANDARDS R3, W9