Short Shakespeare!

Macbeth

January 22

March 5, 2011

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

adapted and directed by David H. Bell

January 22

March 5, 2011

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

adapted and directed by David H. Bell

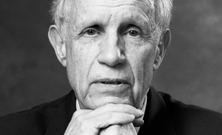

David Bevington is the Phyllis Fay Horton Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in the Humanities at the University of Chicago. A prolific writer and editor, his latest book intended for general readers is This Wide and Universal Theater: Shakespeare in Performance Then and Now.

Macbeth is seemingly the last of four great Shakespearean tragedies—Hamlet (c. 1599–1601), Othello (c. 1603-1604), King Lear (c. 1605-1606), and Macbeth (c. 1606-1607)—that examine the dimension of spiritual evil as distinguished from the political strife of Roman tragedies such as Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, and Coriolanus. Whether or not Shakespeare intended Macbeth as a culmination of a series of tragedies on evil, the play does offer a particularly terse and gloomy view of humanity’s encounter with the powers of darkness.

Macbeth, more consciously than any other of Shakespeare’s major tragic protagonists, has to face the temptation of committing what he knows to be a monstrous crime. Macbeth understands the reasons for resisting evil and yet goes ahead with his disastrous plan. His awareness and sensitivity to moral issues, together with his conscious choice of evil, produce an unnerving account of human failure, all the more distressing because Macbeth is so representatively human. He seems to possess freedom of will and accepts personal responsibility for his fate, and yet his tragic doom seems unavoidable. Nor is there eventual salvation to be hoped for, as there is in Paradise Lost, since Macbeth’s crime is too heinous and his heart too hardened. He is more like Doctor Faustus—damned and in despair.

To an extent not found in the other tragedies, the issue is stated in terms of salvation versus damnation. He, like Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus before him, has knowingly sold his soul for gain. And, although as a mortal he still has time to repent his crimes, horrible as they are, Macbeth cannot find the words to be penitent. “Wherefore could not I pronounce ‘Amen’?” he implores his wife after they have committed the murder. Macbeth’s own answer seems to be that he has committed himself so inexorably to evil that he cannot turn back.

Macbeth is not a conventional morality play (even less so than Doctor Faustus) and is not concerned primarily with preaching against sinfulness or demonstrating that Macbeth is finally damned for what he does. A tradition of moral and religious drama has been transformed into an intensely human study of the psychological effects of evil on a particular man and, to a lesser extent, on his wife. A perverse ambition seemingly inborn in Macbeth himself is abetted by dark forces dwelling in the universe, waiting to catch him off guard.

Among Shakespeare’s tragedies, indeed, Macbeth is remarkable for its focus on evil in the protagonist and on his relationship to the sinister forces tempting him. In no other Shakespearean play is the audience asked to identify to such an extent with the evildoer himself. Richard III also focuses on an evil protagonist, but in that play the spectators are distanced by the character’s gloating and are not partakers in the introspective soliloquies of a man confronting his own ambition. Macbeth is more representatively human. If he betrays an inclination toward brutality, he also humanely attempts to resist that urge. We witness and struggle to understand his downfall through two phases: the spiritual struggle before he actually commits the crime and the despairing aftermath, with its vain quest for security through continued violence. Evil is thus presented in two aspects: first as an insidious suggestion leading Macbeth toward an illusory promise of gain, and then as a frenzied addiction to the hated thing by which he is possessed.

If we consider the hypothetical question, what if Macbeth does not murder Duncan, we can gain some understanding of the relationship between character and fate; for the only valid answer is that the question remains hypothetical—Macbeth does kill Duncan, the witches are right in their prediction. Character is fate; they know Macbeth’s fatal weakness and know they can “enkindle” him to seize the crown by laying irresistible temptations before him. This does not mean that they determine his choice but, rather, that Macbeth’s choice is predictable and therefore unavoidable, even though not preordained. He has free choice, but that choice will, in fact, go only one way.

He is as reluctant as we to see the crime committed, and yet he goes to it with a sad and rational deliberateness rather than in a self-blinding fury. For Macbeth, there is no seeming loss of perspective, and yet there is total alienation of the act from his moral consciousness. Who could weigh the issues so dispassionately and still choose the wrong? Yet the failure is, in fact, predictable; Macbeth is presented to us as typically human, both in his understanding and in his perverse ambition.

We can only hope that the stability to which Scotland returns after his death will be lasting. Banquo’s line is to rule eventually and to produce a line of kings reaching down to the royal occupant to whom Shakespeare will present his play, but, when Macbeth ends, it is Malcolm who is king. The killing of a traitor (Macbeth) and the placing of his head on a pole replicate the play’s beginning in the treason and beheading of the Thane of Cawdor—a gentleman on whom Duncan built “an absolute trust.” Most troublingly, the humanly representative nature of Macbeth’s crime leaves us with little assurance that we could resist his temptation. The most that can be said is that wise and good persons such as Banquo and Macduff have learned to know the evil in themselves and to resist it as nobly as they can.

David Bevington is the Phyllis Fay Horton Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in the Humanities at the University of Chicago. A prolific writer and editor, his latest book intended for general readers is This Wide and Universal Theater: Shakespeare in Performance Then and Now.

David Bevington is the Phyllis Fay Horton Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in the Humanities at the University of Chicago. A prolific writer and editor, his latest book intended for general readers is This Wide and Universal Theater: Shakespeare in Performance Then and Now.