Schiller's

Mary Stuart

February 21

April 15, 2018

CST's Courtyard Theater

in a new version by Peter Oswald

directed by Jenn Thompson

February 21

April 15, 2018

CST's Courtyard Theater

in a new version by Peter Oswald

directed by Jenn Thompson

Charged with conspiracy to commit regicide against England’s queen, her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots, is held captive in Fotheringhay Castle, where she awaits her verdict. The nephew to her guardian in this castle, Mortimer brings news to Mary that the court’s decision is concluded: she is guilty of treason. He reveals to Mary his secret conversion to Catholicism and his allegiance to her. Mary entrusts the young man with two letters: one, addressed to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester—Elizabeth’s beloved favorite and lifelong friend; the second, to her cousin Elizabeth, Queen of England, requesting an audience with her.

Upon reading the letter, Elizabeth asks Mortimer to assume responsibility for the queen’s death, and he gives his consent. Receiving Mary’s letter, Leicester privately confesses that he too supports the Scottish queen, then urges Elizabeth to accept her cousin’s request for a meeting between them. Upon Leicester’s advice, the next day Elizabeth with her retinue sets out to Fotheringhay for the fateful meeting of two queens, both determined to live and to rule.

English translations of Friedrich Schiller’s Mary Stuart are numerous and variant. English playwright Peter Oswald’s 2005 version, commissioned by the Donmar Warehouse in London and published by Oberon Books, is intended as a script for production. It is, in fact, the second of two versions written by Oswald; in 1996, Oxford University Press published his translation of Schiller’s Don Carlos and Mary Stuart in a single edition, intended primarily for an academic audience. Oswald’s 2005 version remains as faithful as possible to the original text, though not at the expense of the play’s poetry. Extensive cutting and the use of a more modern vernacular allowed Oswald to make the script more relevant and accessible to contemporary theatergoers. His changes were strategic: this version, unlike his earlier one, was meant to be performed.

The imagined events of Schiller’s Mary Stuart transpire over the course of a few days, but its story’s roots—and its consequences—begin two centuries earlier in 1377, and “end” in 1603, fifteen years after the play concludes.

The legacy of the Plantagenet king, Edward III (1312–1377) looms over its story. Founder of the dynasty from which both Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots, descend, Edward III is the indirect cause of the struggle for power between these two queens who, through Edward, each asserts her claim to the English throne.

Edward III was a strong, stable, and remarkably fertile English king. He fathered thirteen children—of whom eight were male. But the king’s eldest son and heir apparent, Edward, the Black Prince, died one year prior to his father’s own death when the succession fell to the Black Prince’s oldest living son, crowned Richard II of the House of York.

That might have been the end of the story had it not been for Richard’s Lancastrian cousin, Henry Bolingbroke. In 1399 Henry deposed his Yorkist cousin and assumed the throne as Henry IV. Henry IV managed a successful reign, and the crown passed peacefully to his son, Henry V. But less than a decade into his reign, Henry contracted dysentery and died.

Henry V’s infant son ascended to the throne. Dominated by his courtiers and later by his French wife, Margaret of Anjou, Henry VI proved a weak, ineffective king. Under his reign, England’s claim to France was lost and the crown ran up massive debts. The Yorkists—claiming their right to the throne through two sons of Edward III—grew evermore exasperated with Lancastrian rule.

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1485) commenced—thirty years of civil war in which the crown was passed between the Houses of Lancaster and York. Among this succession of kings was Richard III, who reigned from 1483 to 1485, after declaring his late brother’s marriage invalid and heirs illegitimate.

In 1485 Henry Tudor returned to England from France, where he had been preparing for a rebellion against the Yorkist kings. Henry triumphed, and with Richard III’s death, Henry VII became the first of the Tudor dynasty. A pragmatic ruler, Henry married Elizabeth of York, strategically uniting the houses of Lancaster and York at last. His intentions for the country’s future were symbolized by the name of their first born son: Arthur, England’s king of ancient legend. To protect England against its historic French enemy, Henry allied with Spain and a marriage between Prince Arthur and the Spanish princess, Catherine of Aragon, was arranged.

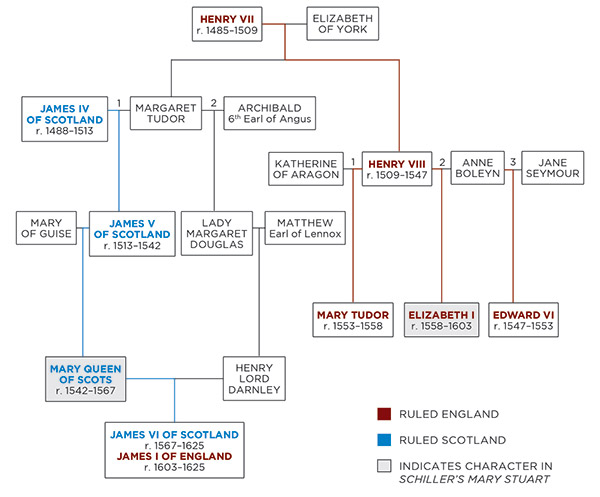

Five months into their marriage, Arthur died. When Henry VII, too, died in 1509, his surviving son ascended to the throne, as Henry VIII. Only with a papal dispensation did Henry marry his brother’s widow and father one living child, named Mary (not the same as Mary, Queen of Scots). Desperate to produce a male heir, Henry broke with the Roman Catholic Church and divorced Catherine in 1533. He quickly remarried the pregnant Anne Boleyn and declared Mary illegitimate. Anne too gave Henry one living heir, the princess Elizabeth, before the queen was charged with a litany of crimes and executed. Elizabeth, too, was subsequently declared illegitimate. His third wife, Jane Seymour, bore the king a son, Edward, before she died of postnatal complications.

Henry’s subsequent three marriages produced no more children. In 1543 his parliament passed the Third Succession Act, which returned both Mary and Elizabeth to the line of succession following Edward. When Henry died in 1547, his nine-year-old son became Edward VII, reigning for just eight years. Not wanting to leave England to the Catholic Mary, Edward and his Protestant advisors tried to divert the succession to Lady Jane Grey, great-granddaughter to Henry VII. The plan failed, and Edward’s eldest half-sister succeeded him as Mary I (“Bloody Mary”), who died a few years later, without issue.

In 1558, Elizabeth I, the last of Henry VIII’s heirs, ascended to the throne, where she would remain until her death in 1603, despite competing claims for the crown: Mary, Queen of Scots, another great-granddaughter to Henry VII, was one of those claimants. Mary’s son, James VI of Scotland, would inherit the English throne, as England’s James I. James—raised away from his Catholic mother in a largely Protestant Scotland—was meant to ensure that England remained beyond the reach of the papacy. The English throne secured James’s silence following his mother’s execution. 1603 marked the end of the Tudor dynasty and the rise of the Stuarts under James I.