WORLD PREMIERE

The Book of Joseph

January 29

March 5, 2017

Upstairs at Chicago Shakespeare

by Karen Hartman

based on the life of Joseph A. Hollander and his family

directed by Barbara Gaines

January 29

March 5, 2017

Upstairs at Chicago Shakespeare

by Karen Hartman

based on the life of Joseph A. Hollander and his family

directed by Barbara Gaines

Here?

by Stuart Sherman

The story told in The Book of Joseph is simple, true, and fraught with loss. In Kraków, Poland, 1939, Joseph Hollander—Jewish, enterprising, and alert to the approaching storm of hate and death—arranges a swift departure to safer places for himself and his large, loved family: mother, sisters, in-laws, nieces. But they decline to leave, calmly convinced that (to echo a novel published three years earlier an ocean away) it can’t happen here. Only Joseph knows it can. They stay; he leaves, intent on securing their escape somewhere down the line.

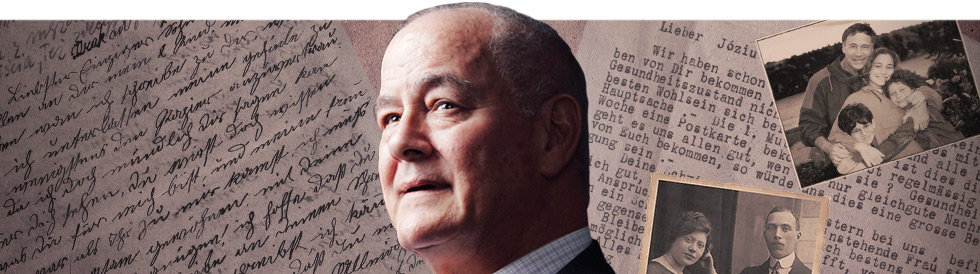

Then there’s a second story, without which we would have far less access to the first. Baltimore, Maryland, 1986: in the wake of Joseph’s death, his adoring grown son Richard finds a briefcase full of letters postmarked from Poland, stamped with swastikas, dating from the early 1940s, written by the Hollanders, under deepening duress, to the their cherished, distant son, now dwelling precariously in America and still trying like hell to get them out.

Entwining these two stories, from the middle and the end of the twentieth century, The Book of Joseph documents the Hollander family’s wholeness and its sunderings. Letters like these index intimacy and distance both at once. If the writers and the reader did not matter so deeply to each other, the letters would not have been written; had the family been all secured in the same place, their interactions would have dissolved in talk, not survived as ink on paper. And because Joseph’s letters have not survived, those in the briefcase travel all one way: a family’s communal attempt, tender and tormented, to bridge the gap between their here and his there.

Performed as play in our still-new century, the letters bridge a gap in time as well as space—from their then to our now. Such temporal crossings, from the present to the past, are always difficult, always incomplete; in the case of the Holocaust, they can seem almost impossible. The numbers alone can numb us—how can we now know what all these dead once knew?

The Book of Joseph, to its enormous credit, tugs hard at this tough question. While Richard Hollander, our wholly American “host” and narrator, celebrates with filial devotion his father Joseph’s astonishing accomplishments, Richard’s sharp son Craig, a history major addicted to archives, questions everything, weighing what little we learn from the letters against the much that we still don’t know of the family’s larger story. For Richard, feeling the cost of the catastrophe is almost everything; for Craig, knowing its intricate history matters more. And in this conversational conflict between father and son—a newer, gentler instance of the Hollander family’s propensity for wholeness and sundering—the playwright mirrors our own difficulties as audience looking back upon the Holocaust at a remove of seven decades: how to grasp, and how to respond to, actions so horrific and losses so immense.

While inhabiting the problem, this play-composed-of-letters also proffers itself as partial solution. Letters, Richard declares at the outset, are “time made manifest.” Plays are too—and like letters, they manifest time most vividly by their devotion to the present tense. Writing from Kraków, the Hollanders framed their every letter to the painful urgencies of the present moment—to what they were enduring now. Plays do the present tense a different way, by means of convergent, palpable presence: the bodies of the actors and the audience, occupying the same space, breathing the same air, hearing and speaking the same words, for the same stretch of time. Today or tonight on Navy Pier, what happened in Kraków generations ago will, in the words and actions of the Hollanders and the performers who play them, happen again, right here right now.

But if plays and letters traffic extensively in the present tense, they deal also, more quietly, in the tensile present—in the ways the present moment is always stretching, via our desires and anxieties, towards the imagined future. In the Hollanders’ letters, as in many others, worries about what comes next can sometimes crowd the present off the page. In plays, too, we are always guessing at what comes next, only to have our expectations confirmed or denied a few scenes down the line. In this way the theater, as Aristotle long ago implied, affords to mortal gazers a vivid, invaluable, rehearsal for the reality we must return to once the play is done.

In 2017, the realities we return to will be exceptionally rigorous. For a map of our present moment we might go back to an older story of another Joseph, the hero at the end of Genesis who (like the hero of our present Book) is forced out of his homeland, only to prosper in a new one. In one of the story’s most striking motifs, Joseph’s spectacular career turns out to be grounded entirely in empathy: for his Egyptian master Potiphar, whom he will not betray; for the Pharaoh whose dreams he productively interprets, to the benefit of all; and for the suffering brothers who once left him for dead, and whom he now welcomes into his new homeland, where the abundance (all that well-stored grain) is in effect of his own making. Yet even the Biblical Joseph’s extraordinary empathy is not sufficient to forestall the cataclysm, generations later, when his descendants in Egypt, newly tyrannized by a subsequent Pharaoh, embark upon their Exodus.

The upshot: oppression and emigration have never stopped; pained propulsion has for too long formed part of the human condition. In 2017, when exodus and the tyrannies that trigger it are transpiring among many peoples across the globe, and empathy seems suddenly in short supply, the theater will function as one among our innumerable, necessary resources for its replenishment: as a space—at once safe and unsettling—in which to foster a ferocious, productive, even disruptive empathy for others, at home and afar, immured or on the run. In the end, Richard and Craig Hollander are both right: all that we know, and all that we feel, will serve as our chief cues for all that we must do, as we exit the theater into a new now, a fraught, tensile present in which it seems, at least for the moment, that anything may happen here.