WORLD PREMIERE

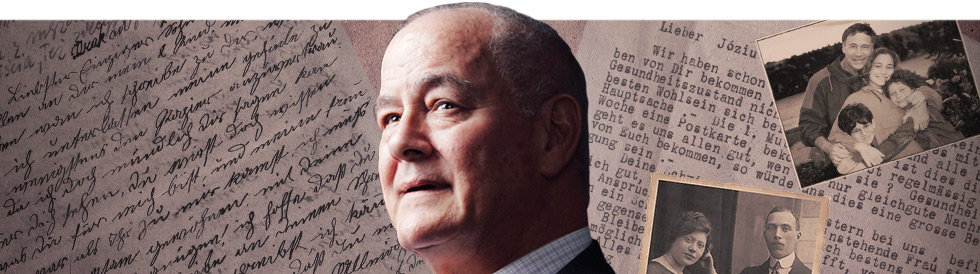

The Book of Joseph

January 29

March 5, 2017

Upstairs at Chicago Shakespeare

by Karen Hartman

based on the life of Joseph A. Hollander and his family

directed by Barbara Gaines

January 29

March 5, 2017

Upstairs at Chicago Shakespeare

by Karen Hartman

based on the life of Joseph A. Hollander and his family

directed by Barbara Gaines

Why was (and is) the telling of your family’s story so imperative to you? What about the telling, the sharing, matters?

Richard Hollander: To me, the word is legacy. Nothing is more important to me than to leave my children and grandchildren memories and values. The Book of Joseph memorializes family memories and is all about instilling values.

Barbara Gaines: Theater’s all about telling stories. It’s been about telling stories since man could talk to each other. The chaos of normal life is put into a kind of order through theater and the chaos of life can weave itself into art. The grief of many people is woven into art and so it helps all of us.

For each of you, what is the single-most important idea that you want audiences to keep thinking about after seeing the Hollander family’s story? (And has that “big idea” shifted for you along the way?)

RH: The briefcase I discovered in my parents’ attic was very real. The briefcase is also a powerful metaphor. Every family and every person has stories and unresolved issues that have been intentionally or unintentionally locked away. Hopefully, the play will inspire the audience to open their “briefcases.”

BG: There are so many lessons to be learned—about family life and silences, about having the courage to excavate not only your family’s interior landscape but your own. Telling a story can free you from the burden of that story.

Richard, what have you learned about your family that you didn’t know? About yourself?

RH: It is gratifying, reassuring, and comforting when one’s image and assumptions about parents are reinforced. All the letters and documentation of my father’s life before I was born validated the extraordinary qualities I always believed he possessed. The passionate words exchanged between my parents confirmed everything I knew about their marriage.

You have used the word “boundaries” to refer to the experience between generations in the letter you wrote to our audiences. Can you say more about that word, and why it carries such meaning for you?

RH: One of the themes in The Book of Joseph concerns deception between father and son—the questions never asked and the answers never given. Unlike the customary use of deception, this deception between father and son was based on mutual love. Parent and child were protecting the emotions of the other. Those boundaries were only broken upon the discovery of the briefcase.

BG: One of the great lessons we learn from the Hollanders is that only through transparency can we have more empathy, to stop judging others and feel for them. When those boundaries are broken down. When you can step over that line—into empathy. You have to shed judgment. That’s what empathy is, isn’t it? It’s a true submersion into the other person’s pain or life. It’s rare.

How did a quote from your grandmother’s letter, “every day lasts a year” become your book’s title?

RH: That one phrase transports me to the ghetto in Kraków. Her words depict the excruciating passage of time waiting for the food that may not come; for exit visas that never arrive; for that inevitable and frightful pounding on the door by Nazi stormtroopers—the wait for rescue and salvation.

The moment that you opened the suitcase, what did you feel? What did you imagine?

RH: One does not have to read Polish or German to know the contents of the letters. I only had to look at the Swastikas stamped on the envelopes to know the letters were from a family I never knew. I couldn’t help but see a parallel between my father having lost his family in war and the violent and simultaneous deaths of my parents.

What difference has the process of living in this story made to each of you?

RH: I feel connected to a family that perished. I feel an overwhelming sense of pride in my father. And, I am far better able to place life’s daily annoyances and issues in perspective.

BG: I’ve come to understand—in a visceral sense—that our ancestors are closer than we think. Getting to know those people who perished in this family, it was impossible not to fall in love with them. They had all the frailties of all of our families, all the petty annoyances, all those things that happen around a family table metaphorically over the lifetime of a family. I don’t know if I’ve ever felt so close to my ancestors whom I’ve never met. This was a big step towards them. My family has been in America for many, many years. I don’t know about the people who lived or died or where they lived or how they lived because everybody was assimilated and wanted to be. Here I am, watching an old country story, and watching a man leave his beloved family to save his life. He tries to save their lives. In their letters, they become so real and so human. They aren’t “simply” part of six million dead, they are individual souls. It’s impossible not to transfer that feeling to my relatives, to all those people generations back that I would like to say thank you to. Thank you for whatever journey you were on. You were the ones who pushed me here through all of your sacrifices and through your spirit of adventure and through your pain, through your successes. That’s why I’m where I am now.