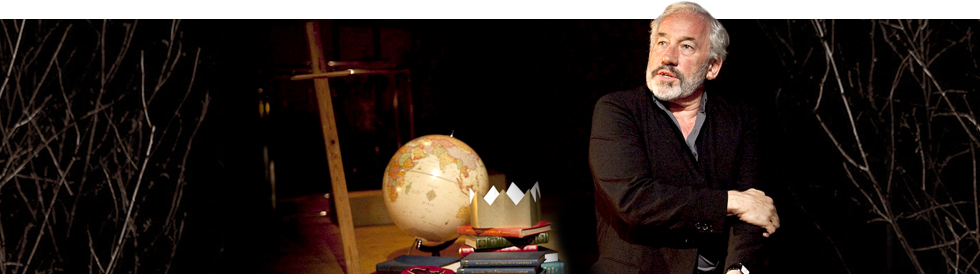

Simon Callow in

Being Shakespeare

April 18 - 29, 2012

at the Broadway Playhouse,

175 E. Chestnut Street, Chicago

A World's Stage Production

from England

by Jonathan Bate

directed by Tom Cairns

April 18 - 29, 2012

at the Broadway Playhouse,

175 E. Chestnut Street, Chicago

A World's Stage Production

from England

by Jonathan Bate

directed by Tom Cairns

by Jonathan Bate

"After God," proclaimed the French novelist Alexandre Dumas, "Shakespeare has created most." "Fantastic!" said Hollywood mogul Samuel Goldwyn on first leafing through the collected works: "And it was all written with a feather!"

So who was William Shakespeare? He was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564. He went to London, became an actor and wrote about 40 plays, two long poems and 154 sonnets. He returned to Stratford and died in 1616, on or around his 52nd birthday. Is that all? How could a mere grammar schoolboy from rural Warwickshire have known enough about courts and kings to write Hamlet and Lear, about Italy to have written The Merchant of Venice, about war to have written Henry V? Where did he get his vast vocabulary and his knowledge of the law? Aren't the surviving documents about his life mysteriously silent about his plays?

It happens every time a Shakespeare scholar reveals his profession in a taxi cab: "Shakespeare expert, are you, guv? Tell me something now—did he write all those plays himself?"

The doubting began two and a half centuries after Shakespeare's death, with an American lady called Delia Bacon. She proposed that the plays were really written by...the philosopher and lawyer Sir Francis Bacon, a proper scholar and courtier. But the unfortunate Delia couldn't find any evidence, so she attempted to dig up Shakespeare's grave in the hope of finding a secret message from Sir Francis. Not long after, her family reported with regret that she had been "removed to an excellent private asylum at Henley-in-Arden—in the forest of Arden"—eight miles from Stratford, as it happens.

Then along came an Edwardian schoolmaster with a new theory: Shakespeare's plays were really written by Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford. That the Earl was an enthusiastic and sometimes violent pederast is not necessarily an impediment to his candidacy. A little local difficulty comes with his death in 1604, before half the plays were written. He would also have had some difficulty collaborating with the actors during the long period when he was in exile abroad for having committed the unpardonable offence of farting in front of Queen Elizabeth. The schoolmaster's name? J Thomas Looney.

But there's no shortage of other candidates: 8th Lord Mountjoy, 7th Earl of Shrewsbury, 6th Earl of Derby, 5th Earl of Rutland, 2nd Earl of Essex, Sir Walter Raleigh, the Countess of Pembroke, Queen Elizabeth I and King James I. These names seem to have something in common. It all boils down to snobbery, the conviction that such high genius could not have come from a lowly place. Americans, including Mark Twain of all people, have often taken this line, which is curious in a country where it's supposed to be possible to go from a log cabin to the White House.

Conspiracy theorists dismiss the man from Stratford as an imposter. They suppose that he was an illiterate actor mouthing some greater man's words. But they cannot explain away the facts.

In his will, Master William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon left legacies to his fellow- actors John Hemmings and Henry Condell. They in turn edited the First Folio of his collected works, referring there to his writing techniques and their close friendship with him. The First Folio also includes poems by Ben Jonson attesting to the authentic likeness of the engraving of Shakespeare on the title-page, to Shakespeare's authorship of the plays and to his coming from Stratford ("Sweet swan of Avon", Jonson calls him). Shakespeare acted in Jonson's plays, which often quote from his work. In both his notebook and his conversations with the Scottish poet Drummond of Hawthornden, Jonson also spoke about Shakespeare as a writer (sometimes critically!). Many other contemporaries also referred to Shakespeare as a poet and playwright. They range from Sir George Buc, Master of the Revels at court, to other dramatists such as Francis Beaumont and Thomas Heywood, to Leonard Digges, a family friend of Shakespeare's who was also a writer himself. Shakespeare's monument in Holy Trinity Church refers to his literary greatness. It was seen by a visiting poet soon after his death, negating the claim of some conspiracy theorists that it was altered at a later date.

How did a man who did not go to university write such 'learned' plays? They are actually much less learned than the plays of his contemporaries George Chapman and Ben Jonson, neither of whom went to university. The simple fact is that the education in Latin language and literature that Shakespeare got at the Stratford grammar school puts our modern curriculum to shame.

How did he know about courts, how to see into the minds of dukes and kings? Through his reading and through witnessing the court by acting there. Payments to him for writing plays for court performance survive in the chamber accounts of the royal household. Better questions would be: how could anyone but a glover's son have put in his plays so much accurate technical detail about leather manufacture and the process of glove-making?

And how could anyone but a professional actor have filled his plays with inside information about the nitty-gritty of making theatre?

Plays are not autobiographical confessions. Shakespeare did not fill his works with portraits of his acquaintances (though he occasionally makes joking references to members of his own acting company and to friends such as his schoolmate Richard Field, who became the publisher of his first printed work). What we can unearth in the plays is better described as the experiential DNA of the author. A life split between country and city, Stratford and London; a grammar school education (the bright but cheeky schoolboy called William in The Merry Wives of Windsor might just be a witty self-portrait); a precocious and varied love life; the direct experience of witnessing recruiting officers mustering for the militia in rural Warwickshire and Gloucestershire; some basic legal language learned from a life of litigation; above all, a constant awareness that all the world's a stage, all the men and women merely players. The seven ages of man are at one and the same time the seven ages of Everyman and of that unique genius named William Shakespeare.

Disappointing as it is to acknowledge, the mighty dramatist was provincial and middle-class, and his life was distinctly uneventful. His rival Christopher Marlowe moved in a world of espionage, thuggery, buggery and skulduggery. His collaborator George Wilkins had a second career as a brothel-keeper with a history of beating up the girls who worked for him. And as for Ben Jonson, who was both a friend and a rival: he fought in the Dutch wars, killed a fellow actor in a street brawl and was thrown into prison for writing subversive plays.

Will Shakespeare was neither a fabulous aristocrat nor a flamboyant gay double agent. He was a grammar school boy from an obscure town in middle England, whose main concern was to keep out of trouble and to better himself and his family. He came from a perfectly unremarkable background. That's the most remarkable thing of all.

Maybe it was because Shakespeare was a nobody that he could become everybody. He speaks to every nation in every age because he understood what it is to be human. He didn't lead the life of the pampered aristocracy. He was a working craftsman who had to make his daily living and to face the problems that we all face every day. His life was ordinary—it was his mind that was extraordinary. His imagination leapt to every corner of the earth and every age of history, through fantasy and dream, yet it was always rooted in the real.

He shows us what it is to be human. But what was it like being Shakespeare? That is the question we ask in our play.