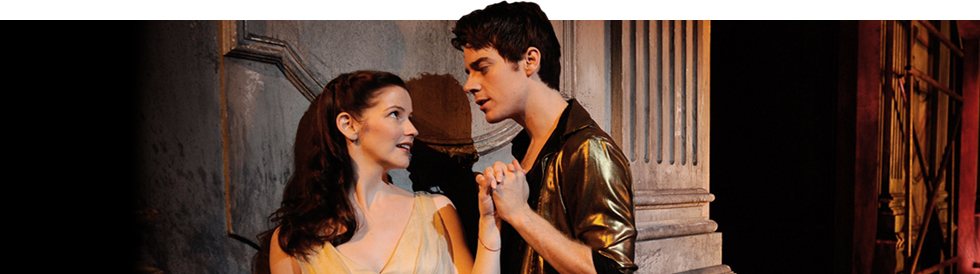

Romeo and Juliet

September 15

November 11, 2010

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Gale Edwards

September 15

November 11, 2010

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Gale Edwards

We all know something about tragedy: we lose someone we love; we must leave a place we don't want to leave; we make a mistake of judgment that leads to consequences we never imagined. Tragedy is a part of our lives as humans—no matter how much we wish to avoid it and its pain. So why read tragedy? Why come to see a tragic play at the theater? What point is there in entering, by choice, so dark a world? Clearly, it's more fun to watch Stephen Colbert than to read Romeo and Juliet. So why do it?

We respond to stories that show us people who are somehow like us, versions of ourselves under different circumstances. In other words, we can best understand characters who bear some resemblance to us. And because they are somehow like us, we become interested in them, and often sympathize with them. But when a story is really communicating to us, it goes one step beyond touching our sympathy. As we come to understand the people on the page or on the stage, we can also reach some understanding about our own world—about ourselves and the people with whom we interact—and about the tragedies we have to face.

Shakespeare's tragic plays, like our own lives, are stories that interweave opposites—joy and sorrow, farce and harsh reality. How often in a day do we experience both of these extremes? Until its third act turning point, Romeo and Juliet behaves very much like a romantic comedy: complete with intrigues, go-betweens, obstacles in the lovers' way, an inflexible, traditional society impeding the freedom of the younger generation, and an older generation who does not speak the same language. But the play turns on the murder of Mercutio; suddenly, it is drained of its bawdiness, its wit, and playfulness. Tragedy follows. Shakespeare personifies this truth with a mastery few writers can hope to attain.

Where and how do we find our story here? To begin to answer this, we might first look at some of the common threads in what we call "tragedy." Often the characters face some very difficult choices, and the story follows them as they wrestle with making their decisions. In tragedy, the hero often faces some "fearful passage" (taken from the Prologue of Romeo and Juliet)—a path traveled for the first time where old answers and old behaviors are suddenly not sufficient. The stakes are very high, and the risk to the individual, to the family&madsh;and sometimes to an entire society, as in Romeo and Juliet—is great.

There is much discussion in literature about the tragic hero and his inherent "tragic flaw." Shakespearean scholar Russ McDonald warns that in labeling the hero as inherently weak and not up to the challenge, we're inclined to judge him critically. But the heroes of tragedy typically display great strengths, says McDonald. Their tragedy lays not so much in a weakness of character, but in a "kind of tragic incompatibility between the hero's particular form of greatness and the earthly circumstances that he or she is forced to confront." McDonald points out how differently the heroes of Shakespeare's tragedies speak, not only from us, but also from all the other characters around them. Their poetic language, he says, expresses their "vast imaginations." They see the world more completely than the rest of us.

Tragic figures imagine something extraordinary, and seek to transcend the compromises of the familiar; we both admire that imaginative leap and acknowledge its impossibility. The contest between world and will brings about misery, insanity, and finally death; it also produces meaning and magnificence.

Through their journeys, the tragic hero and heroine learn something about themselves and about their lives. It is understanding that comes, however, from tremendous loss and pain. It has been noted by some scholars that in Romeo and Juliet, the earliest of Shakespearean tragedies, the hero and heroine do not learn so much from their tragic path as the survivors and the city they leave behind. It is the suffering of Verona through the consequences of its violence that leads to wisdom and reconciliation. In this sense, according to David Bevington, the community itself becomes a protagonist in this early play. In his later tragedies, those lessons are internalized into the consciousness of Shakespeare's heroes and heroines through their tragic journeys.

In our own lives, we may never face the same choices that Romeo and Juliet must. But it is very likely that we will face choices that seem too big for us to handle. We will be required to go through some "fearful passage" of our own where old ways of thinking and behaving don't work. We will face head-on the consequences of choices we've made—and wish desperately that what's done might be undone.

What makes art different from life is exactly that. What's done can be undone—or even prevented when it comes to our own lives. This tragedy is temporary. We close the book. We leave the theater. If we enter that world and come to know its characters, we come to know ourselves. The damage that is permanent and irreversible to tragedy's heroes is reversible and temporary for us as witnesses. And when our own "fearful passage" comes along, we will have learned along the way about ourselves and the nature of others, and be able to make our choices with the benefit of their experiences.