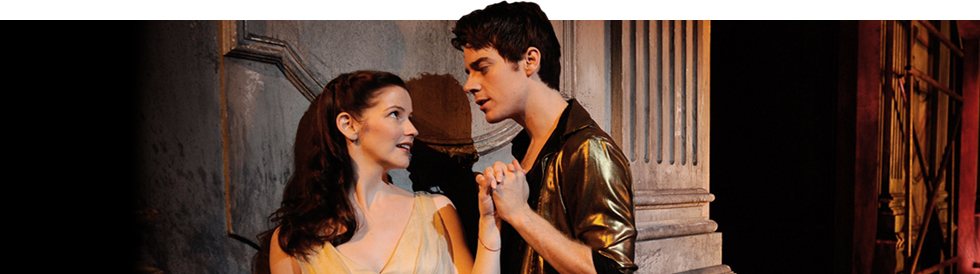

Romeo and Juliet

September 15

November 11, 2010

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Gale Edwards

September 15

November 11, 2010

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Gale Edwards

Romeo and Juliet is in many ways a familiar story, not just because it is one of Shakespeare's best-loved plays, but because the play has thematic roots in myths as old as storytelling itself. A man and a woman fall in love; they are young and beautiful, and their love is so consuming that the world and all the people around them seem to vanish. The young woman dies, or appears to die, and her grief-stricken lover determines to win her back from death, either by his wits or by joining her in the afterlife. In some versions of the story he succeeds, though only for a time. The themes of the story—love, death, resurrection, and death again—are clearly present in a myth like Orpheus and Eurydice: when Eurydice dies, her lover Orpheus defies Death and brings her back from the underworld, only to lose her again when he doubts his success. Another myth with similar themes is that of Demeter and Persephone, though it concerns a mother and daughter instead: death has kidnapped Demeter's beloved daughter Persephone, and Demeter fights him until he allows her to have Persephone back for half of every year. Myths like these are present in almost every culture.

As far as scholars can tell, Shakespeare used only one source for his version of Romeo and Juliet: a narrative poem by the sixteenth-century English poet Arthur Brooke, entitled The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet. The origins of Brooke's poem can be traced back to the second century AD, to a romance called the Ephisiaca, by Xenophon of Ephesus. In Xenophon's story, two teenagers—Anthia and Habrocomes—fall in love at first sight and they marry. But when Anthia is rescued from robbers by Perilaus, he too wants to marry her. Attempting to kill herself in order to avoid marrying Perilaus, Anthia drinks a potion that she believes to be poison, but rather than dying, she falls into a deathlike sleep. Habrocomes visits her tomb to mourn, and eventually the lovers are reunited, living happily ever after.

The Ephesiaca holds many familiar sections for readers of Romeo and Juliet: a hidden marriage, a second suitor, a potion that causes the appearance of death, and a scene in a tomb. By the fifteenth century, the story that Brooke would tell in his poem had acquired more recognizable elements. Masuccio Salernitano's Cinquante Novelle of 1476 tells of the romance between Mariotto and Gianozza. The lovers are secretly married by a friar; Mariotto is banished for killing another citizen; Gianozza's father chooses a husband for her and she goes to the friar for help. He gives her a sleeping potion, which she drinks; she appears to be dead and is entombed. Although she has sent a note to her husband, he does not receive it. Anguished by reports of his wife's death, Mariotto rushes home, only to be arrested at her tomb and put to death. Gianozza subsequently dies of grief.

At least three other versions of this story were written between Salernitano's and Brooke's, and each included elements that would become essential in Shakespeare's tragedy. The first and most influential is Luigi da Porto's 1530 version. In it, he renames the lovers Romeo Montecchi and Giulietta Capelletti; he calls the friar Lorenzo. Da Porto introduces a character called Marcuccio, a friend of Romeo's (noted only for his icy hands); and identifies the man whom Romeo kills as Theobaldo Capelletti. Da Porto's story adds the ball, the balcony scene, and the lovers' double suicide at Giulietta's tomb—which Giulietta accomplishes by holding her breath! Matteo Bandello's 1554 Novelle gave the Nurse the significant part that she plays in Shakespeare's retelling. In 1559 Pierre Boiastuau had Romeo go to the Capulets' ball in hopes of seeing his unrequited love, whom Shakespeare would later call Rosaline. Boiastuau was the first to write of Juliet's grief when her husband murders her cousin Tybalt, and his version was the first in which the character of the Apothecary appears.

Arthur Brooke's poem The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet, published in 1564, adheres to the framework constructed in the previous stories, filling it in a bit with more developed characters and relationships. He adds the character of Benvolio, and concentrates on deepening relationships, such as Juliet's to her father, and the Nurse's to the lovers. Brooke's poem slightly expands the role of Mercutio, paving the way for Shakespeare to develop one of his most fascinating characters. About 35 years later, c. 1597, William Shakespeare would write the version of Romeo and Juliet that today remains the best known and loved.

Why is Shakespeare's play the one we remember? His story is quite similar to Brooke's poem—adapting Brooke's plot, characters, and sometimes even his characters' speeches. What makes Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet a classic while da Porto's Novelle and Brooke's Tragicall Historye are obscure artifacts? What ensures the survival of one retelling rather than another?

Shakespeare used the English language with a precision and an imagination that no other playwright has achieved, before or since. Lines like "Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?" or "Parting is such sweet sorrow" may seem clichéd now, but their familiarity is a testament to their lyrical—and lasting—power. Another essential difference between Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet and the earlier versions is the development of character and plot. Shakespeare recreates each character, filling out the framework of the story so that each character—even the ones who appear only briefly, like Peter—seems like a person we know. When Juliet proclaims her love to Romeo, she speaks it beautifully; the exchange between them feels almost too perfect, until she wonders aloud if she should have been "more strange"—in other words, kept her true feelings private. We've all had the feeling of having said too much, and we know how she feels.

Shakespeare also gives a social context to his love story, setting the play in a Verona that is bawdy and bustling with life. The private scenes between the lovers capture us, in part, by the way they are brilliantly set against other scenes so full of people and action that we hardly know where to focus our attention. Romeo and Juliet create a private world of love into which Shakespeare allows us to enter; he brings us so close that we feel their agony, even after we close the book or leave the theater. Using Verona and the families' feud as background, Shakespeare brings us into the intimate story of the lovers. Like the writers before him, Shakespeare touches on eternal themes of love, death, hatred and reconciliation; unlike others, Shakespeare helps us understand where these themes dwell in our own lives.