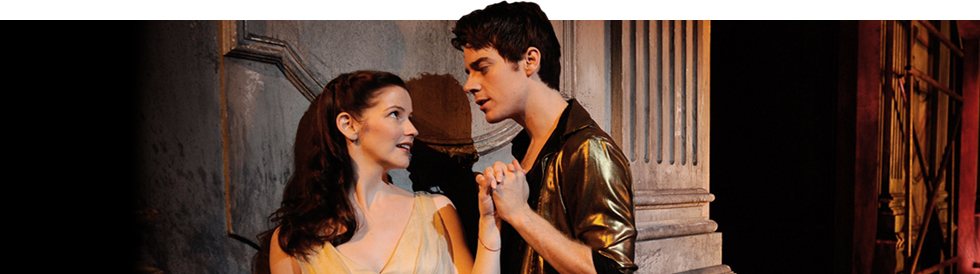

Romeo and Juliet

September 15

November 11, 2010

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Gale Edwards

September 15

November 11, 2010

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Gale Edwards

Australian guest director Gale Edwards discusses her production of Romeo and Juliet.

Gale Edwards: We tend to think of Romeo and Juliet as a love story and a tragedy because two people fall in love and kill themselves in the end. Of course, that's true; that's what happens. But I think this play is about much more than that. At its center is our seeming need as human beings to create the Other...the Enemy, and to perpetuate conflict. In this play, one generation inherits the anger and violence of their parents. It might just as well be passed along in the mother's milk. No one even remembers who started the war or why. They're just fighting and they've been fighting for as long as anyone can remember. (Does all this sound familiar?) Tybalt does exactly what he's been brought up to do. The strangers in this world are Romeo and Juliet—because they're still able to love, to contact something very simple, but searingly pure, and to cross the boundary of hatred, suspicion and fear.

CST: And so this play's iconic stature as "the greatest love story ever told" is not, for you, where its center lives?

GE: Yes, this is a gorgeous, iconographic love story, set against a world that doesn't understand it and won't allow it. Theirs is a lyrical love affair. The play is written mainly verse. It is highly poetic writing. But it's also a play about generations. The parent generation fails the lovers at every turn. Even the two loving co-conspirators, Friar Laurence and the Nurse, who set out to help the lovers, abandon their surrogate children at the end. And that tension and lack of understanding between the generations is at the center of the play.

CST: Would you describe the world of this play as you imagine it?

GE: The play is full of imagery of light and dark, night and day, heaviness and lightness. The dark (night) is the friend of the lovers, the searing light of day is the enemy to love. When we are first introduced to Romeo, he is absorbed in the darkness of his romantic musings over Rosaline. Juliet brings light into his darkness. Night and darkness make up the lovers' world. It's where they seek refuge. Romeo speaks of a "lightning before death," and this phrase, for me, became the metaphor for the play. Lightning is referred to many times in the text—lightning that spectacularly lights up the sky and is then gone. Like lightning, everything moves with enormous, and unpredictable, velocity. Events happen. Suddenly somebody's killed, suddenly there's a duel, a letter isn't delivered, suddenly...It is a play that catapults into the abyss of tragedy, and I want that sense of anarchic urgency embodied in our production. No one actually "thinks" too deeply in this play. There is a dangerous, unadvised spontaneity in almost all the choices the characters make. I'm interested in this story moving forward "Too like the lightning which doth cease to be / Ere one can say 'it lightens.'" We've opened up the space in the theater and created a long runway, all the way to the back wall. I want to create a world in which the play can feel athletic and muscular. It creates a very exciting, physical dynamic.

CST: With the cast at first rehearsal, you talked about taking a "filmic" approach to Shakespeare. What does that mean?

GE: I do believe that if Shakespeare lived today he would very happily write movie scripts. He'll pick up a scene halfway through and has no problem with walking people on to the stage starting somewhere in mid-sentence. He'll cut between locations: First we're in Juliet's bedroom, then we're in the streets, then we're somewhere else. I like to trust the filmic approach that Shakespeare would have relied on at the Globe where, as one group of people is coming off, the next group is coming on. The place is changed by imagination. How you use the space becomes the production's filmic "cut." So I became fascinated with how the use of space, and the words, determine the place we are in.

CST: So how did that approach then become realized in working with your scenic designer, Brian Sidney Bembridge, to create a physical world?

GE: I'm interested in set as metaphor. I'm not interested in creating a realistic town square with columns and archways. I don't think Shakespeare needs it. These plays were born on a simple, little wooden "O" of the Globe Theatre—and they were played in contemporary clothes, i.e. the same clothes the Elizabethan audience was wearing. They don't need television naturalism. Instead, the world is described by the characters through poetry and through imagination, which is infinitely more powerful than anything we can deliver physically on stage.

Verona in our production is neither golden sandstone nor sunny. It's a shadowy dark world, in which Juliet is the sun, the light illuminating the darkness. I wanted a world that was once glamorous, but now is disintegrating, decaying due to neglect. The physical world of the set, though once beautiful, reflects the kind of moral decline of the characters in the play. Because they are consumed and distracted by the feud that fuels their lives, many things are neglected by these wealthy, feuding dynasties. We've created a place that was architecturally beautiful in the past but is now a damaged, crumbling world. There's bits of scaffolding, there are corners crumbling off, and somebody has had the "forethought" to install modern, metal roller-doors, now covered in graffiti. Without a great deal of care, the modern world has been imposed on top of this elegant world of the past, now violated and perched on destruction.