A time of historical transition, of incredible social upheaval and change, the English Renaissance provided fertile ground for creative innovation. The early modern period stands as the bridge between England’s very recent medieval past and its near future in the centuries commonly referred to as the Age of Exploration, or the Enlightenment. When the English Renaissance is considered within its wider historical context, it is perhaps not surprising that the early modern period produced so many important dramatists and literary luminaries, with William Shakespeare as a significant example.

Because of its unique placement at a crossroad in history, the English Renaissance served as the setting for a number of momentous historical events: the radical re-conception of the English state, the beginnings of a new economy of industry, an explosion of exploration and colonialism, and the break with traditional religion as the Church of England separated from the Catholic Church. It is perhaps this last example of cultural upheaval—the changes brought from Continental Europe by the Protestant Reformation—that provides us with a useful lens to examine the theatrical situation in England during this period, in particular.

While we can see that Shakespeare lived through a transitional time, and we can understand that rapid change often fosters innovation, we may still be led to ask what could have influenced Shakespeare’s dramatic sensibilities. What kind of theater did he encounter as a child or a young man that may have made an impression upon him? It is commonly acknowledged by scholars today that Shakespeare may have developed his love for the theater by watching acting troupes that were still traveling from town to town during the middle decades of the sixteenth century—the early modern successors to a long heritage of English theater carried over from the Middle Ages. These traveling performers often enacted important stories from the Bible, staged tales of mystery and miracles, or presented their audiences with the stories of the lives of saints and heroes of the faith.

These traveling companies would move around the countryside in flatbed, horse-drawn carts, which did triple duty as transportation, stage, and storage for props and costumes. They would pull into a town square, into an inn yard or the courtyard of a country estate or college, and transform that space into a theater. People gathered around to watch, some standing on the ground in front of the players’ stage, some leaning over the rails from balconies above to view the action on the impromptu stage below.

But during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries as the Protestant Reformation gained a surer footing in England, the English theater was caught between conflicting ideas about the value and purpose of drama. Many officials of the Protestant Reformation desired to squash these traveling performances for their strong Catholic sensibilities; and even as late as 1606 James I passed legislation to remove all treatment of religious matters from the English playhouses.

But as the stories enacted in the newly constructed public theaters became more secular, public officials scorned the theater as immoral and frivolous. The theaters just outside London’s walls came to be feared as places where moral and social corruption spread. The authorities frequently shut them down during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, when the city was menaced by the plague and, frequently too, by political rioting. When the theaters were open, the Master of the Revels had to read and approve every word of a new play before it could be staged. But of course the practical enforcement of such measures was often sketchy at best, and playing companies themselves found plenty of ways around the strictures of the theatrical censors.

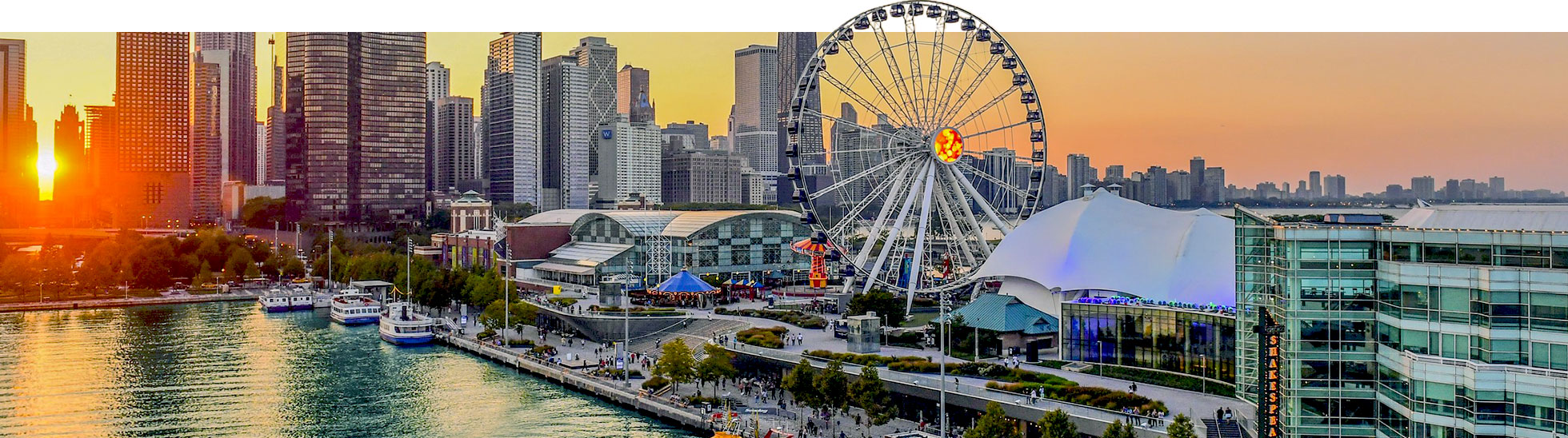

A man who would later become an associate of Shakespeare’s, James Burbage, built the first commercial theater in England in 1576, in the decade prior to Shakespeare’s own arrival on the London theater scene. Burbage skirted rigid restrictions governing entertainment in London by placing his theater just outside the city walls, in a community with the unglamorous name of “Shoreditch.” Burbage was not the only one to dodge the severe rules of the Common Council of London by setting up shop in Shoreditch. His neighbors were other businesses of marginal repute, including London’s brothels and bear-baiting arenas. Actors in Shakespeare’s day were legally given the status of “vagabonds.” They were considered little better than common criminals unless they could secure the patronage of a nobleman or, better still, the monarch. Shakespeare and his fellow actors managed to secure both. They provided popular entertainment at Queen Elizabeth I’s court as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, and they continued to enjoy court patronage after King James I came to the throne in 1603, when they became the King’s Men. Their success at court gave Shakespeare and his fellow shareholders in the Lord Chamberlain’s company the funds to build the new Globe playhouse in 1599. The Globe then joined a handful of other theaters located just out of the city’s jurisdiction as one of the first public theaters in England. All kinds of people came to plays at the Globe, and they came in great numbers--a full house in the Globe could see as many as 3,000 people. The audience typically arrived well before the play began to meet friends, drink ale, and snack on the refreshments sold at the plays. An outing to the theater was a highly social and communal event and might take half the day. It was more like tailgating at a football game, or going with friends to a rock concert, than our experience of attending theater today. Affluent patrons paid two to three pence or more for gallery seats (like the two levels of balcony seating at Chicago Shakespeare Theater), while the “common folk”—shopkeepers, artisans, and apprentices—stood for a penny, about a day’s wages for a skilled worker. The audience of the English Renaissance playhouse was a diverse and demanding group, and so it is often noted that Shakespeare depicted characters and situations that appealed to every cross-section of Renaissance society. Audience appeal was a driving force for the theater as a business venture and so, during this period, most new plays had short runs and were seldom revived. The acting companies were always in rehearsal for new shows and, because of the number of ongoing and upcoming productions, most plays were rehearsed for just a few days.

There was, of course, no electricity for lighting, so all plays were performed in daylight. Sets and props were bare and basic. A throne, table or bed had to be brought on stage during the action since English Renaissance plays were written to be performed without scene breaks or intermissions. For example, when stage directions in Macbeth indicate that “a banquet is prepared,” the stage keepers likely prepared the banquet in full view of the audience. From what scholars can best reconstruct about performance conventions, Shakespeare’s plays were performed primarily in “contemporary dress”— that is, the clothes of Shakespeare’s time—regardless of the play’s historical setting. Company members with tailoring skills sewed many of the company’s stock costumes, and hand-me-downs from the English aristocracy often provided the elegant costumes for the play’s nobility. Because women were not permitted to act on the English stage until 1660, female roles were performed by boys or young men, their male physique disguised with elaborate dresses and wigs. The young actors were readily accepted as “women” by the audience.

After an extremely productive creative period spanning about 100 years--often called the “Golden Age” of the English theater—the Puritans, now in power of the government, succeeded in 1642 in closing the theaters Altogether. The public theaters did not reopen until the English monarchy was restored and Charles II came to the throne in 1660. A number of theaters, including the Globe, were not open very long before the Great Fire of London destroyed them in 1666. The fire, combined with the eighteen years of Commonwealth rule—the so-called Interregnum (“between kings”)--led to the loss of many of the primary sources that would have provided us with further evidence of the staging traditions of Shakespeare’s theater. The new theater of the Restoration approached plays, including Shakespeare’s, very differently, often rewriting and adapting original scripts to suit the audience’s contemporary tastes. So it is left to scholars of early modern English drama to reconstruct the practices of Renaissance theater from clues left behind.