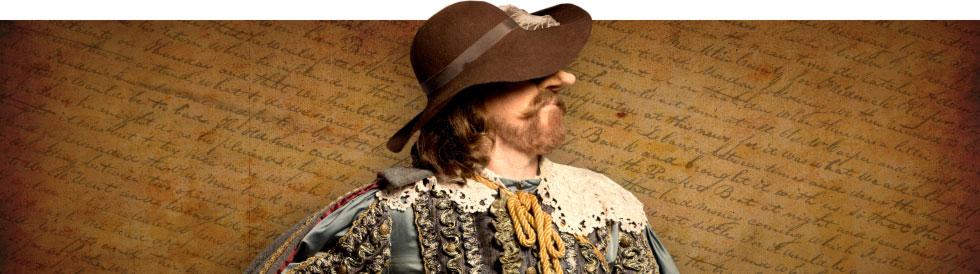

Cyrano de Bergerac

September 24

November 10, 2013

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by Edmond Rostand

translated and adapted for the stage

by Anthony Burgess

directed by Penny Metropulos

September 24

November 10, 2013

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by Edmond Rostand

translated and adapted for the stage

by Anthony Burgess

directed by Penny Metropulos

Rostand’s play has received criticism at times for not being true enough to the “real story” of Cyrano. Sure, there are differences between Rostand’s imagined world and historical events, but art and history are two separate endeavors. A playwright’s project is to tell a story, to move an audience--and, hopefully, to fill the theater. History can serve as a frame or structure to reinforce an artist’s blank canvas, but creative license liberates them from the past’s mandates. The historian’s concern with facts, events and data conveys one sort of truth. The artist’s undertaking is still aimed at discovering and communicating truth—but it’s a truth that transcends the details of time and place and attempts to answer our larger, more abiding human questions.

The real Cyrano was born in 1619 in the French capital, a Parisian without any Gascon lineage—unlike his fictional counterpart. His family, of Italian roots, owned estates in the southwestern region of France. From an early age, his formal education was a trying experience, fueling what would become a growing distaste for clergy, teachers and authority. At nineteen, having completed his schooling, he joined his friend Henri Le Bret in an army company almost wholly composed of Gascon soldiers. While enlisted, he gained a reputation as an accomplished, though hotheaded, swordsman and dueler. Despite his prowess, he was wounded in the siege of Arras in 1640, taking a sword to the throat. He recovered, but never returned to the full flourish of his earlier days.

Cyrano left the king’s service and turned to a life dedicated to learning, meditation and writing. He studied under some of the most renowned philosophers of the day, frequented literary circles with the likes of Molière, and became a fixture in the cultural life of Paris. The fervor and zeal with which he had undertaken his military career was now channeled to his pen. His writings ushered in the early modern era, providing a key link between earlier French works and those that follow in the Enlightenment. To the chagrin of the clerical powers of the time, they also endorsed the principles of freethought, reliance upon reason alone. He worked under the patronage of the Duc d’Arpajon, who produced the only one of Cyrano’s plays ever seen in a performance—at which, unfortunately, the audience broke out in rioting in reaction to the work’s perceived sacrilege. Still, his written corpus is notable: it contains the first example of a jet-propelled spacecraft (a firecracker-powered vehicle that goes to the moon and the sun), which later served as an influence upon Jonathan Swift and Voltaire, among others.

And what about that nose? The historical Cyrano did, in fact, have a large nose, though nowhere near the proportions made manifest in the dramatic work bearing his name. His temperament was said to be fiery and easily provoked. There’s a general lack of certainty regarding his amorous pursuits: some speculate that he was too engrossed in studies to pursue women, others that he may have been homosexual. Whatever the truth, there is broad consensus that he was not enamored with his cousin, Madeline, as the play would suggest. He died at the early age of thirty-six after enduring fourteen months of concussion-induced illness. The cause of his head trauma: a falling timber.

—Contributed by CST Education Department