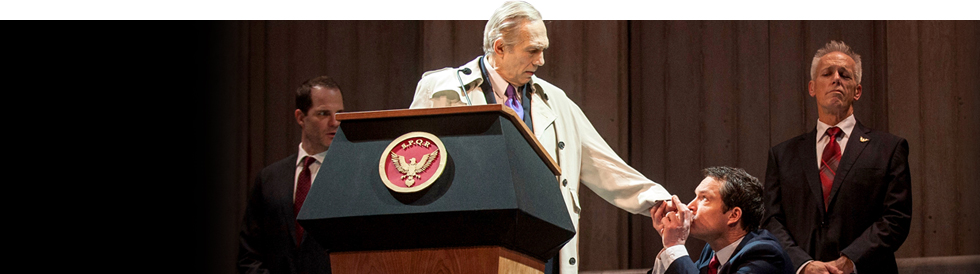

Julius Caesar

February 5

March 24, 2013

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Jonathan Munby

February 5

March 24, 2013

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Jonathan Munby

by Michael Dobson

Never mind that fleeting reference to Bermuda in The Tempest: Shakespeare's American play is Julius Caesar. Admittedly, the United States didn't exist when Shakespeare wrote it, but the long process by which at least part of the English-speaking world would eventually become a republic was already under way. And when we hear Cassius imagining the states unborn and accents yet unknown in which the killing of Caesar will continue to be enacted in the distant future, it is hard not to feel that Shakespeare was being even more prescient than usual.

By 1599, when Shakespeare wrote Julius Caesar, Elizabeth I had been queen for over forty years, and there was still no obvious heir apparent. Shakespeare, meanwhile, had just composed what would be the last of his plays about the English crown, Henry V, which concludes with the Chorus remarking that its hero's successes all come to nothing when the throne, thanks to a mere accident of heredity, passes to his politically incompetent son Henry VI. According to Shakespeare's history plays, monarchical rule is usually a recipe for civil strife and succession crises, and when the playwright turned to the subject matter of the Roman state instead he was not the only person looking for alternatives in the classical past. The Earl of Essex, for instance, a close associate of Shakespeare's patron the Earl of Southampton, was showing a conspicuous interest in the Roman republic and empire--and within two years he would attempt a coup d'etat against Elizabeth.

Little more than thirty years after Shakespeare's death a much more successful attempt at drastic constitutional change took place with the execution in 1649 of Charles I—a king whom some of the parliamentarians who deposed him called 'Caesar,' styling themselves as 'Senators.' The ensuing English republic collapsed only a decade later, but the dream of a more rational constitution, based on the models espoused by the likes of Cicero and Cassius, lived on, nourished in part by the continuing currency of Shakespeare's play. Again flattering parliamentarians by the title of their ancient Roman counterparts, the theater critic Francis Gentleman wrote in 1773 that Julius Caesar should be made their official text:

We wish that our senators, as a body, were to bespeak it annually; that each would get most of it by heart; that it should be occasionally performed at both universities, and at every public seminary, of every consequence; so would the author receive distinguished, well-earned honour; and the public reap, we doubt not, essential service.

Preserving the ideals of Shakespeare's Brutus among MPs and at the elite schools and universities that educated them, though, was all very well for Shakespeare's reputation among the British establishment, though it seemed unlikely to transform the state. But in the same year another, rather pithier text appeared that sought to take the play's republicanism back onto the streets. Not the streets of London, however, but those of a city farther west whose attachment to this play, in some quarters at least, was rather more militant. A 1773 broadside addressed to the citizens of Boston, Massachusetts, rallying the people against unfair taxes and unrepresentative government as it announces the arrival of certain ships bearing cargoes of ill-fated tea, begins with a familiar rhetorical formula: 'Friends, brethren, countrymen…'

Julius Caesar, then, was part of the American Republic from its very inception, and as the United States set about designing its neoclassical constitution and the gargantuan neo-Roman buildings which would give it palpable form (buildings that now include, suitably enough, the Folger Shakespeare Library) this drama of political aspiration and ambition continued to bed in. In 1787 Philadelphia, Peter Markoe hailed Julius Caesar as Shakespeare's masterpiece, proof that this freedom-loving author now belonged to the States:

Monopolizing Britain! boast no more

His genius to your narrow bounds confin'd;

Shakespeare's bold spirit seeks our western shore,

A general blessing for the world design'd,

And, emulous to form the rising age,

The noblest Bard demands the noblest Stage.

If Markoe's country has indeed inherited the political ideals that animate this play's conspirators, it has also inherited the irreconcilable conflicts that provoke its violence. Like Caesar, certain US presidents have been seen by some as the Constitution's illegitimate and tyrannical masters rather than its servants: Abraham Lincoln, most famously, was killed by an assassin, John Wilkes Booth, who as well as being a supporter of one of Rome's less appealing institutions – slavery – was an actor whose favorite role was that of Brutus. In a country perpetually in danger of becoming an empire too large for real democracy, whose (overwhelmingly male) leaders transact their business and enact their rivalries between the Capitol and the Senate, Julius Caesar, for better and for worse, is always going to look right at home. The elections may happen in November, but presidents should still keep a lookout for the ides of March.

Michael Dobson is Director of the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon and Professor of Shakespeare Studies at the University of Birmingham, UK. A former associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, in 1995 he played Henry VIII for Barbara Gaines in the Chicago Humanities Festival.

Michael Dobson is Director of the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon and Professor of Shakespeare Studies at the University of Birmingham, UK. A former associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, in 1995 he played Henry VIII for Barbara Gaines in the Chicago Humanities Festival.