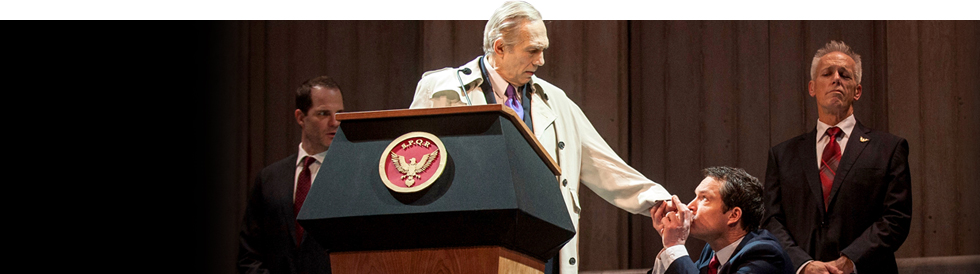

Julius Caesar

February 5

March 24, 2013

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Jonathan Munby

February 5

March 24, 2013

in CST's Courtyard Theater

by William Shakespeare

directed by Jonathan Munby

by Martha Nussbaum

Julius Caesar shows us two different kinds of love, in tragic opposition. Although it would be easy to see Brutus as a cold man who acts on principle, Shakespeare repeatedly emphasizes his intense compassion for Rome and all Romans, threatened with bondage by a charismatic and unprincipled populist tyrant. Brutus tells us that one strong emotion has driven out another emotion (personal love of Caesar), as fire drives out fire. He appeals to the emotions all Romans have, he thinks, for their threatened republican form of government. He addresses them as "countrymen and lovers," summoning them to love of country and hatred of oppression. Reason and love are not at odds for him, because he intensely loves the causes that he also thinks rational argument can justify. He expects all Romans to be like him: deliberative citizens, who value liberty with both their judgment and their hearts. (Were Antony Caesar's own son, Brutus says earlier, the conspirators’ compelling moral arguments should satisfy him.) Shakespeare brilliantly gives him prose not poetry at this crucial moment, but a passionate rhythmic prose, the language of general compassion.

Shakespeare's sources, the ancient authors Plutarch and Suetonius, support this picture of Brutus as a man of philosophical principle, whose motives in leading the plot against Caesar were untainted by personal grievance or envy. The author of well-known books on virtue and duty, he really was the moral philosopher putting his ideas into practice. Brutus was not a Stoic, as he is often said to be, but a Platonist; he auditioned possible conspirators by asking them whether civil war was preferable to "lawless monarchy"—Plato's technical designation of the worst possible regime. Shakespeare suppressed the one bit of personal gossip the sources do mention, the possibility that Brutus may have been Caesar's natural son. According to Suetonius, Caesar's last words were, in Greek, "You too, my child" (kai su, teknon)—in place of which Shakespeare gives us "Et tu Brute", "You too, Brutus," a reminder of personal friendship rather than of kinship.

Brutus' antitype is Antony, the dissolute and unprincipled, who can understand no kind of love other than the personal, who cannot refrain from calling the dead man "Julius" even in the presence of the conspirators, and whose "O pardon me, thou bleeding piece of earth" spills out over this world of philosophically moralized emotion like a red stain. For him, the Servant gives proof of a "big heart" only by being dumbstruck at the sight of Caesar's corpse. Antony can understand that Brutus is honorable and fine; Brutus' type of passionate love he cannot grasp. In one sense Antony's heart is large; in another, it is pinched and small.

Julius Caesar is the play's dramatic center because he is the focal point of this collision of loves—the charismatic object of Antony's and the people's devotion, the merely personal love against which Brutus must fortify himself in pursuit of his passion for justice. As in the sources, Caesar is a populist tyrant, who loved the people and took bold steps to improve their economic circumstances, but at the price of political liberty. Daring commander, epileptic, erudite author, statesman who more than anyone might have saved the Roman Republic had he not loved glory more—these contradictory aspects of the man are indelibly etched in Shakespeare's spare portrait.

The citizens of Rome resemble Antony, not Brutus, in their loves. That is Brutus' tragedy, and theirs, and Rome's. The play poses one of the darkest questions of political life: can Brutus' type of love ever motivate masses of people or determine the course of events? And, if it cannot, what lies in store for human freedom?

Martha Nussbaum is the Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics at the University of Chicago, appointed in the Law School and Philosophy Department. She writes on Greek and Roman philosophy, on political justice, and on the emotions. Her current book in progress is Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice, to be published in 2013

Martha Nussbaum is the Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics at the University of Chicago, appointed in the Law School and Philosophy Department. She writes on Greek and Roman philosophy, on political justice, and on the emotions. Her current book in progress is Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice, to be published in 2013