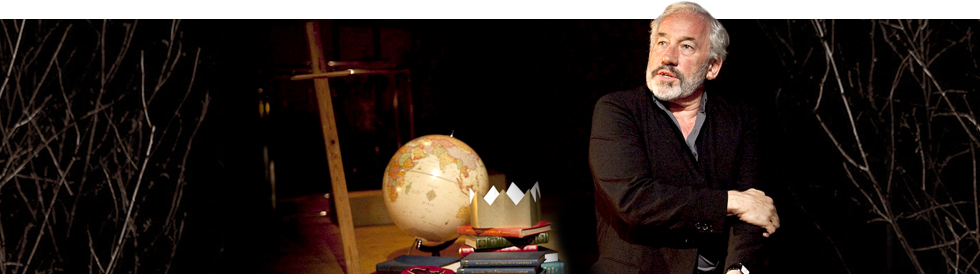

Simon Callow in

Being Shakespeare

April 18 - 29, 2012

at the Broadway Playhouse,

175 E. Chestnut Street, Chicago

A World's Stage Production

from England

by Jonathan Bate

directed by Tom Cairns

April 18 - 29, 2012

at the Broadway Playhouse,

175 E. Chestnut Street, Chicago

A World's Stage Production

from England

by Jonathan Bate

directed by Tom Cairns

by Simon Callow

I'm six. My mother is the secretary of a school deep in the Berkshire countryside. The headmaster's mother, Mrs Birch, a hirsute, full-breasted old Cockney whom I adore, and on whose breath there is always the sickly scent of sweet sherry, gathers me up onto her hospitable lap and switches on the radio. Spooky music. The announcer says, in his crisp cut-glass accent, Mecbeth, A Play by William Shakespeare. It was scary and very strange, this Mecbeth, and thank God for Mrs Birch's ample bosom into which I could sink for comfort. I realise now that this was the first play I ever saw, and I use the word "saw" advisedly. The images conjured up, of battlements and blasted heaths, of witches and kings, of murdered children and dead men walking, compounded by the sound of wind and rain and marching feet, haunted by the music of the words, most of which I could barely understand, installed themselves in my brain and have never left them. A certain landscape, Shakespeare's landscape, entered my consciousness, like a dream that is more vivid than experience itself. Scholars talk of the Shakespeare Moment, meaning the moment in time, the crossroads—historical, linguistic, theatrical—at which Shakespeare stood; but my personal Shakespeare Moment was then, in that cosy room in Goring-on-Thames, on that familiar lap, enveloped by the scent of that sweet warm breath. Ever after, I craved the poetry, the power, the sense of history, of great conflicts, and of the other world—the overwhelming atmosphere, in a word—that this astonishing writer purveyed.

My family were not notable theatregoers, nor were they even very great readers, but like most British people of the time, they had a Complete Works of Shakespeare on the bookshelf. This particular one belonged to my maternal grandmother, another ample-bosomed, sweet-breathed, spirited old personage, and was a rather splendid affair, in three volumes—Comedies, Tragedies and Histories— edited by Dr Otto Dibelius of Berlin, and illustrated with Victorian black and white engravings. As a no doubt somewhat overwrought 12-year old I would stretch out on the tiger-skin rug in the front room with the precious volumes, reading aloud from them, weeping passionately at the beauty and the majesty of it all, though I had only the vaguest idea of what it was that I was saying. Big emotions, big beautiful phrases, big expansive characters—it was a better world than any my daily life afforded me, that was for sure.

Then school did its best to destroy my love of Shakespeare by reducing him to a Set Subject. Oddly, there were no school plays at my school, although the elocution teacher worked with us on some scenes from A Midsummer Night's Dream, and I was cast as Bottom and began to get very serious about it, when the whole thing was abandoned as being too ambitious. Perhaps it was I who was too ambitious, and the other kids got bored with my incessant questions and requests to do the scene just once more. Otherwise whenever I could swing it, I took the leading parts in the ghastly droned, fluffed, misinflected classroom readings of the plays during English lit classes.

I had at last seen some of the plays. My paternal grandmother had some personal connection with the Box Office Manager of the Old Vic in its dying days, in the early 1960s, and there I saw the good honest productions of that time, and began to realise something of the diversity of this author, the different worlds—so very different from that of Macbeth—that he had brought to life. And I began to hear the language more and more precisely, not as undifferentiated music but as a succession of images and metaphors with a life of their own.

In 1963, Laurence Olivier arrived at the Vic, and what had been black and white (more often grey, in fact) was suddenly Technicolor. The company he created were all high-definition performers, none more so than himself. He prowled the stage like a puma, orchestrating the language with the trumpets and piccolos and high strings that in his own voice, swooping down on particular phrases and branding them indelibly into memory. His fellow actors were not far behind him, Robert Stephens, Maggie Smith, Albert Finney, the young lions Jacobi, McKellen, Hopkins, Gambon. We lived in a sort of Shakespearean paradise in those days. And I consumed as much of it as I possibly could.

I cannot remember experiencing any great curiosity about Shakespeare himself, however. The conventional wisdom was that everything known about him could be written in the back of a cigarette packet, and I accepted this. At a certain point, a friend of my grandmother's, a wise old bird from Bavaria called Ilse Andter, gave me a bijou silk- covered edition of the Sonnets. I was 18 and not entirely sorted out sexually; maybe she thought I might find some clues in its pages. I started reading the Sonnets in sequence from the beginning, but was daunted by verbal and narrative obscurities, and by the lack of any thread one could follow. There were some sensational sexual ambiguities ("O thou my lovely boy"—who was talking to whom?), but they were tantalising rather than titillating. From time to time, one would come across a famous poem—"Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?" or "Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediment"—and these I cherry- picked, rather as one might select the chocolates with soft centres from one's box of Milk Tray; but it never occurred to me that the Poems might tell me anything about Shakespeare himself.

In due course I left school. Inspired by yet another astounding performance at the Old Vic, I impulsively wrote a letter to Laurence Olivier and he wrote back by return of post offering me a job in the Box Office, and from that vantage point I was able sometimes to sneak into rehearsals; once, from the shadows at the back of the stalls, I spied on him working on his Shylock. Inevitably, I conceived a desire to act. But the school I attended, fine though it was, had a very un-English bias against Shakespeare, preferring Ben Jonson, so when, five years out of Drama School, I came to play the title role in Titus Andronicus at the Bristol Old Vic, it was as a Shakespeare virgin.

Some deflowering! But it was then and only then— wrestling with this astonishing play during the course of which the youthful author graduates from bombast to some of his profoundest explorations of grief and madness—that I became deeply interested in the man who could have created it. I started to conjure a Shakespeare for myself. I thought of him as a quintessential actor, absorbing everything around him, shifting shape, adapting face and voice to whoever he was addressing, uniquely available to emotion. The deep craving for stability, so central to the plays, explained the apparently incongruous facts of his quest for a coat of arms and his determination to buy the grand house of New Place in Stratford.

It was As You Like It, as it happens, that took me back to the National, on stage instead of in the Box Office, and it was while I was playing Orlando that Michael Kustow, head of Platform Performances, called me to say that he'd just read a new re-ordering of the Sonnets by a psychoanalyst called John Padel which suggested that they were a record of a profound personal experience. Would I like to be part of a group of actors who performed them in the new order? I would, I said, and then two minutes later I called him back and said, in the full flush of my youthful megalomania, that surely if we thought the poems were autobiographical, it should be just one actor, and surely that one actor should be me? We embarked on a series of programmes at the National which climaxed one afternoon in a performance of all 154 poems in a sold-out Olivier Theatre in which Sir John Gielgud rather prominently sat, scaring the life out of me. I have often performed the Sonnets since, and it has never been less than overwhelming; and I've played Falstaff (twice), overwhelming in a quite different way. For some years, now, I have been exploring Charles Dickens, the man, and it has been a profoundly exhilarating experience. Approaching Shakespeare the man is quite as intense but in some ways more ambitious: we know less, and the work is even greater. Being Shakespeare is a voyage of discovery for me which I have found deeply affecting, because he deals with nothing less than all of human life.

This article is an extract from Simon's book My Life in Pieces.